The 5 Most Poisonous Jellyfish

The huge submerged ecosystem we call the ocean is home to many species of animals and plants. It’s also one of the most unexplored parts of planet Earth and is home to many poisonous invertebrates such as the jellyfish. In this article, we’ll be looking at the most poisonous jellyfish around.

The name jellyfish already causes a certain amount of fear in itself, as these invertebrates are associated with pain due to their sting. However, not all species within this group are poisonous. In order to make this distinction correctly, we’ll look at why jellyfish are poisonous, as well as looking at the 5 most poisonous jellyfish of all and how to recognize them

Why are jellyfish poisonous?

Although jellyfish are harmless-looking animals, nothing could be further from the truth. Evolution has allowed them to develop defensive techniques, such as the production of a highly toxic venom.

At an evolutionary level, the main function of jellyfish toxicity is related to a defensive role. Several studies have determined that the composition of the venom contains substances that are dangerous to humans.

If humans are exposed to high doses of these substances, they can suffer great harm. Even low dose reactions are lethal to their prey and harmful to us.

The 5 most poisonous jellyfish

Here are five jellyfish, classified as extremely poisonous. Knowing a little more about them will help us to identify them and put us on guard when we see them. Don’t miss it!

1. Sea nettle jellyfish

Among all the existing jellyfish species, the sea nettle jellyfish or Chrysaora fuscescens certainly stands out. Specimens of this species are easily spotted due to their size – 1.80 meters (nearly 6 feet) – and their golden-brown hue.

One of their most striking features is their ability to locate the light. Thanks to it, they can detect prey or possible threats. In addition, they’re capable of releasing a reddish-colored ink.

Due to their intense colors and easy maintenance for humans, this species is often exhibited in public aquariums. Fortunately, its sting is only irritating to humans, although there have been cases that have caused more danger.

2. Sea wasp

Despite its small size, it’s estimated that just 1.4 milliliters of the venom of the sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri) could kill a human being within minutes. For this reason, it holds first place on the podium of dangerous jellyfish, and is classified as the most poisonous toxic species on Earth.

It’s around 6 millimeters (0.25 inches) in diameter, but its tentacles can reach 3 meters (nearly 10 feet) in length. The danger of this invertebrate lies in the size of its tentacles, as humans can be grazed by them and be stung. However, this animal prefers the waters far from the shore of Australian beaches.

A curious fact about its sting is that, according to a study published on the portal Science Direct, the older the specimen, the more potent its venom. In addition, other researchers are studying the pharmacological usefulness of jellyfish venoms in the hope of developing drugs.

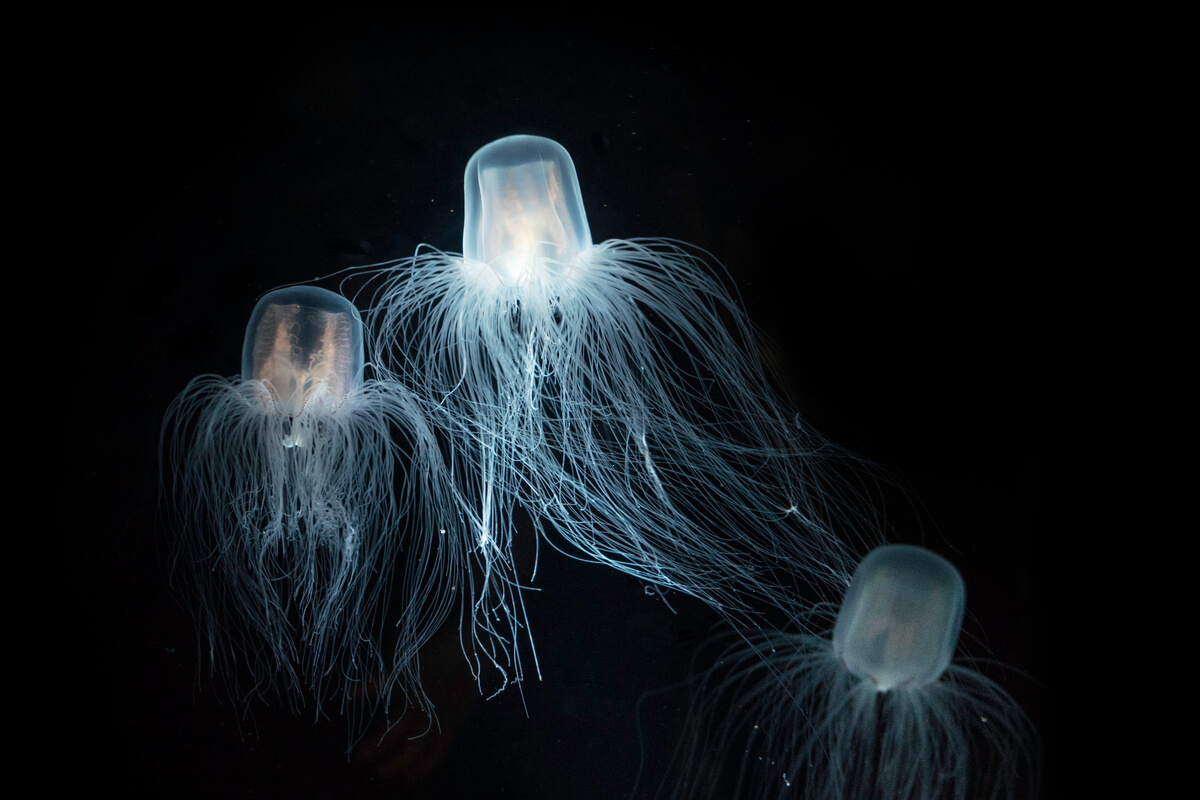

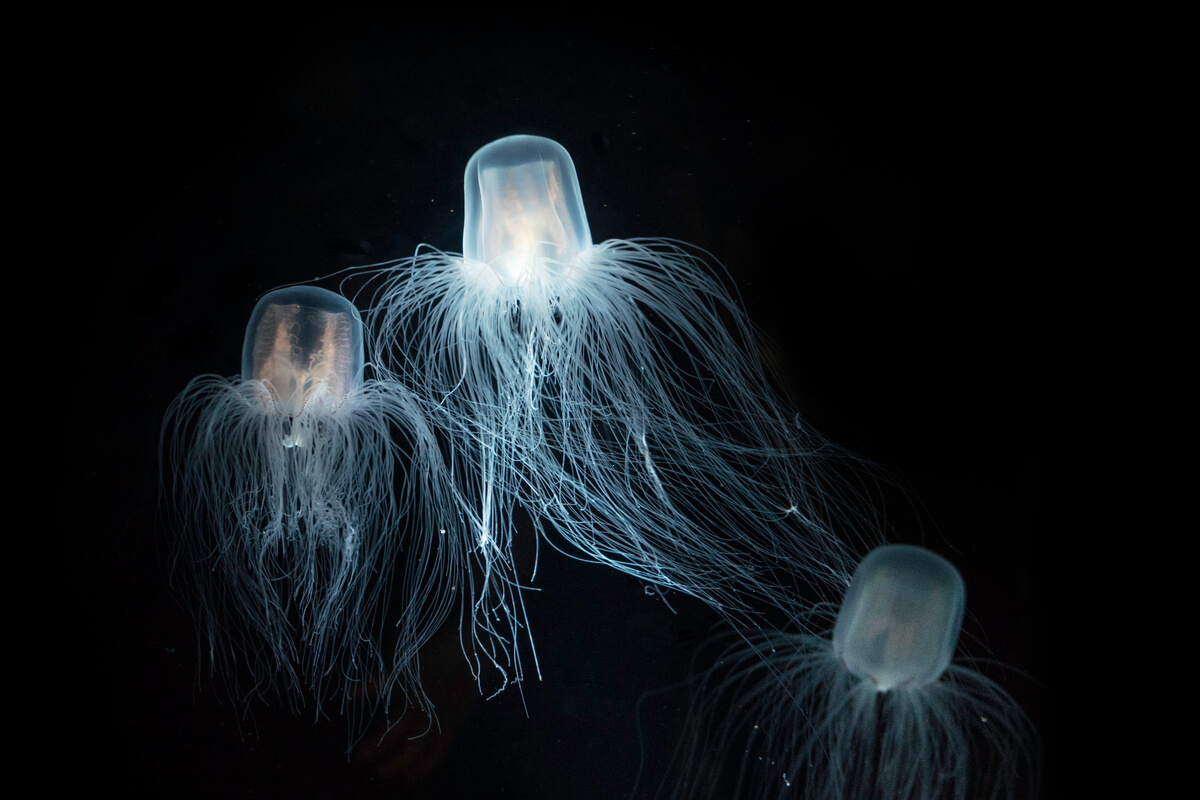

3. Irukandji jellyfish

Its name comes from the inhabitants located in the north of Australia, called Irukandji. Along with the sea wasp, it belongs to the cubomedusae and the Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) is also right at the top of the list for toxicity.

Its venom is reportedly 100 times more potent than that produced by a cobra. Despite being one of the smallest jellyfish species, it has been observed that the smaller it is, the more potent the toxicity of its sting.

The most common symptoms of its sting include muscle cramps, a burning sensation, vomiting, headache, or tachycardia. The set of symptoms has been called the “Irukandji syndrome”. Fortunately, the sting isn’t lethal if the victim receives proper treatment in time.

4. Lion’s mane jellyfish

The species Cyanea capillata, known as the lion’s mane jellyfish, or giant jellyfish, has been identified as the world’s largest jellyfish. Its bell can reach 2.5 meters (6.5 feet) and its tentacles can reach an incredible 30 meters (100 feet)! To complete this fearsome scenario, it can weigh a quarter of a ton.

Typical of cold waters, it’s found in the North Atlantic Ocean and Australian waters. Like other jellyfish, its nematocytes remain active even when dead. This means that they can cause stings some time after their death.

5. Portuguese Man o’ war

Although the Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) isn’t technically a true jellyfish, but we simply had to include it in this list. Every year, this invertebrate seems to hit the news, due to numerous specimens found stranded on the beaches.

Unfortunately, after becoming stranded, these animals end up dying on the seashore. However, their death doesn’t mean there’s no risk of a sting. Their tentacles seem to remain active, even if they’re separated from the body or the specimen is dead.

As already mentioned, this “false jellyfish” is actually a colony of hydrozoans, also called a colonial organism. It’s easily recognizable thanks to its pinkish color with bluish tones. We wanted to include it on this list, as its sting can be fatal to humans.

In short, the oceans that make up the Earth’s large bodies of water are home to many different species. Today, we’ve spoken about jellyfish and, in particular, the most poisonous species.

However, here at My Animals, we’ve got a wealth of articles about all types of marine and terrestrial life – take a look and you’re sure to find articles to pique your interest. Check out the end of this post and you’ll find one we’ve selected for you!

Knowing all about these jellyfish, means that you can act quickly and sensibly if you should find one. The most important thing is to get as far away as possible from their tentacles, where the stinging cells loaded with venom are located.

The huge submerged ecosystem we call the ocean is home to many species of animals and plants. It’s also one of the most unexplored parts of planet Earth and is home to many poisonous invertebrates such as the jellyfish. In this article, we’ll be looking at the most poisonous jellyfish around.

The name jellyfish already causes a certain amount of fear in itself, as these invertebrates are associated with pain due to their sting. However, not all species within this group are poisonous. In order to make this distinction correctly, we’ll look at why jellyfish are poisonous, as well as looking at the 5 most poisonous jellyfish of all and how to recognize them

Why are jellyfish poisonous?

Although jellyfish are harmless-looking animals, nothing could be further from the truth. Evolution has allowed them to develop defensive techniques, such as the production of a highly toxic venom.

At an evolutionary level, the main function of jellyfish toxicity is related to a defensive role. Several studies have determined that the composition of the venom contains substances that are dangerous to humans.

If humans are exposed to high doses of these substances, they can suffer great harm. Even low dose reactions are lethal to their prey and harmful to us.

The 5 most poisonous jellyfish

Here are five jellyfish, classified as extremely poisonous. Knowing a little more about them will help us to identify them and put us on guard when we see them. Don’t miss it!

1. Sea nettle jellyfish

Among all the existing jellyfish species, the sea nettle jellyfish or Chrysaora fuscescens certainly stands out. Specimens of this species are easily spotted due to their size – 1.80 meters (nearly 6 feet) – and their golden-brown hue.

One of their most striking features is their ability to locate the light. Thanks to it, they can detect prey or possible threats. In addition, they’re capable of releasing a reddish-colored ink.

Due to their intense colors and easy maintenance for humans, this species is often exhibited in public aquariums. Fortunately, its sting is only irritating to humans, although there have been cases that have caused more danger.

2. Sea wasp

Despite its small size, it’s estimated that just 1.4 milliliters of the venom of the sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri) could kill a human being within minutes. For this reason, it holds first place on the podium of dangerous jellyfish, and is classified as the most poisonous toxic species on Earth.

It’s around 6 millimeters (0.25 inches) in diameter, but its tentacles can reach 3 meters (nearly 10 feet) in length. The danger of this invertebrate lies in the size of its tentacles, as humans can be grazed by them and be stung. However, this animal prefers the waters far from the shore of Australian beaches.

A curious fact about its sting is that, according to a study published on the portal Science Direct, the older the specimen, the more potent its venom. In addition, other researchers are studying the pharmacological usefulness of jellyfish venoms in the hope of developing drugs.

3. Irukandji jellyfish

Its name comes from the inhabitants located in the north of Australia, called Irukandji. Along with the sea wasp, it belongs to the cubomedusae and the Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) is also right at the top of the list for toxicity.

Its venom is reportedly 100 times more potent than that produced by a cobra. Despite being one of the smallest jellyfish species, it has been observed that the smaller it is, the more potent the toxicity of its sting.

The most common symptoms of its sting include muscle cramps, a burning sensation, vomiting, headache, or tachycardia. The set of symptoms has been called the “Irukandji syndrome”. Fortunately, the sting isn’t lethal if the victim receives proper treatment in time.

4. Lion’s mane jellyfish

The species Cyanea capillata, known as the lion’s mane jellyfish, or giant jellyfish, has been identified as the world’s largest jellyfish. Its bell can reach 2.5 meters (6.5 feet) and its tentacles can reach an incredible 30 meters (100 feet)! To complete this fearsome scenario, it can weigh a quarter of a ton.

Typical of cold waters, it’s found in the North Atlantic Ocean and Australian waters. Like other jellyfish, its nematocytes remain active even when dead. This means that they can cause stings some time after their death.

5. Portuguese Man o’ war

Although the Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) isn’t technically a true jellyfish, but we simply had to include it in this list. Every year, this invertebrate seems to hit the news, due to numerous specimens found stranded on the beaches.

Unfortunately, after becoming stranded, these animals end up dying on the seashore. However, their death doesn’t mean there’s no risk of a sting. Their tentacles seem to remain active, even if they’re separated from the body or the specimen is dead.

As already mentioned, this “false jellyfish” is actually a colony of hydrozoans, also called a colonial organism. It’s easily recognizable thanks to its pinkish color with bluish tones. We wanted to include it on this list, as its sting can be fatal to humans.

In short, the oceans that make up the Earth’s large bodies of water are home to many different species. Today, we’ve spoken about jellyfish and, in particular, the most poisonous species.

However, here at My Animals, we’ve got a wealth of articles about all types of marine and terrestrial life – take a look and you’re sure to find articles to pique your interest. Check out the end of this post and you’ll find one we’ve selected for you!

Knowing all about these jellyfish, means that you can act quickly and sensibly if you should find one. The most important thing is to get as far away as possible from their tentacles, where the stinging cells loaded with venom are located.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Becerra-Amezcua, M. P., González-Márquez, H., Guzmán-Garcia, X., & Guerrero-Legarreta, I. (2016). Medusas como fuente de productos naturales y sustancias bioactivas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Farmacéuticas, 47(2), 7-21. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/579/57956610002.pdf

- Bengston, K., Nichols, M. M., Schnadig, V., & Ellis, M. D. (1991). Sudden death in a child following jellyfish envenomation by Chiropsalmus quadrumanus: case report and autopsy findings. JAMA, 266(10), 1404-1406. Disponible en: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/391769

- D’Ambra, I., & Lauritano, C. (2020). A Review of Toxins from Cnidaria. Marine Drugs, 18(10), 507. Disponible en: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/18/10/507

- Feng, J., Yu, H., Li, C., Xing, R., Liu, S., Wang, L., … & Li, P. (2010). Isolation and characterization of lethal proteins in nematocyst venom of the jellyfish Cyanea nozakii Kishinouye. Toxicon, 55(1), 118-125. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19619571/

- Jouiaei, M., Yanagihara, A. A., Madio, B., Nevalainen, T. J., Alewood, P. F., & Fry, B. G. (2015). Ancient venom systems: a review on cnidaria toxins. Toxins, 7(6), 2251-2271. Recuperado de: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26094698/

- Kimball, A. B., Arambula, K. Z., Stauffer, A. R., Levy, V., Davis, V. W., Liu, M., Wingfield, ;., Rehmus, E., Lotan, A., & Auerbach, P. S. (2004). Eficacia de un inhibidor de picadura de medusa en la prevención de picaduras de medusa en voluntarios normales. Safesea.Es. Disponible en: https://safesea.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Wilderness-and-Environmental-Medicine-Eficacia-SafeSea.pdf

- Ponce-Garcia, D. P. (2017). Transcriptomic, proteomic and biological analyses of venom proteins from two Chrysaora jellyfish (Doctoral dissertation, University of Melbourne).

- Ramasamy, S., Isbister, G. K., Seymour, J. E., & Hodgson, W. C. (2005). The in vivo cardiovascular effects of the Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) nematocyst venom and a tentacle extract in rats. Toxicology letters, 155(1), 135-141. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15585368/

- Scott-Frías, J., & de Jorquera, E. M. (2020). La Fragata Portuguesa o Aguamala (Physalia physalis): Importancia en la salud pública. Revista bionatura, 5(4), 1418-1422. Disponible en: https://revistabionatura.com/files/2020.05.04.24.pdf

- Underwood, A. H., & Seymour, J. E. (2007). Venom ontogeny, diet and morphology in Carukia barnesi, a species of Australian box jellyfish that causes Irukandji syndrome. Toxicon, 49(8), 1073-1082. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17395227/

- Warrell, D. A. (2013). Animals hazardous to humans. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease, 938. DIsponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7152310/

- Winter, K. L., Isbister, G. K., Seymour, J. E., & Hodgson, W. C. (2007). An in vivo examination of the stability of venom from the Australian box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri. Toxicon, 49(6), 804-809. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0041010106004636

- Winter, K. L., Fernando, R., Ramasamy, S., Seymour, J. E., Isbister, G. K., & Hodgson, W. C. (2007). The in vitro vascular effects of two chirodropid (Chironex fleckeri and Chiropsella bronzie) venoms. Toxicology letters, 168(1), 13-20. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17141433/

- Winter, K. L., Isbister, G. K., McGowan, S., Konstantakopoulos, N., Seymour, J. E., & Hodgson, W. C. (2010). A pharmacological and biochemical examination of the geographical variation of Chironex fleckeri venom. Toxicology letters, 192(3), 419-424. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378427409015331

- Xiao, L., He, Q., Guo, Y., Zhang, J., Nie, F., Li, Y., … & Zhang, L. (2009). Cyanea capillata tentacle-only extract as a potential alternative of nematocyst venom: Its cardiovascular toxicity and tolerance to isolation and purification procedures. Toxicon, 53(1), 146-152. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19026672/

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.