Why Are There Ants With Wings?

Written and verified by the biologist Samuel Sanchez

Surely you’ve seen ants with wings, right? Strange as it may seem, this event isn’t a mistake of nature or an atypical occurrence, as it responds to the reproductive mechanism of the vast majority of social hymenopterans. The massive emergence of winged ants at ideal times when it comes to temperature and humidity is known as nuptial flight and is fascinating.

Ant colonies generally live underground or in decaying logs, but from time to time, some winged individuals must be born so that the dispersion of genes occurs beyond the anthill itself. If you want to know more about this topic, we encourage you to keep reading.

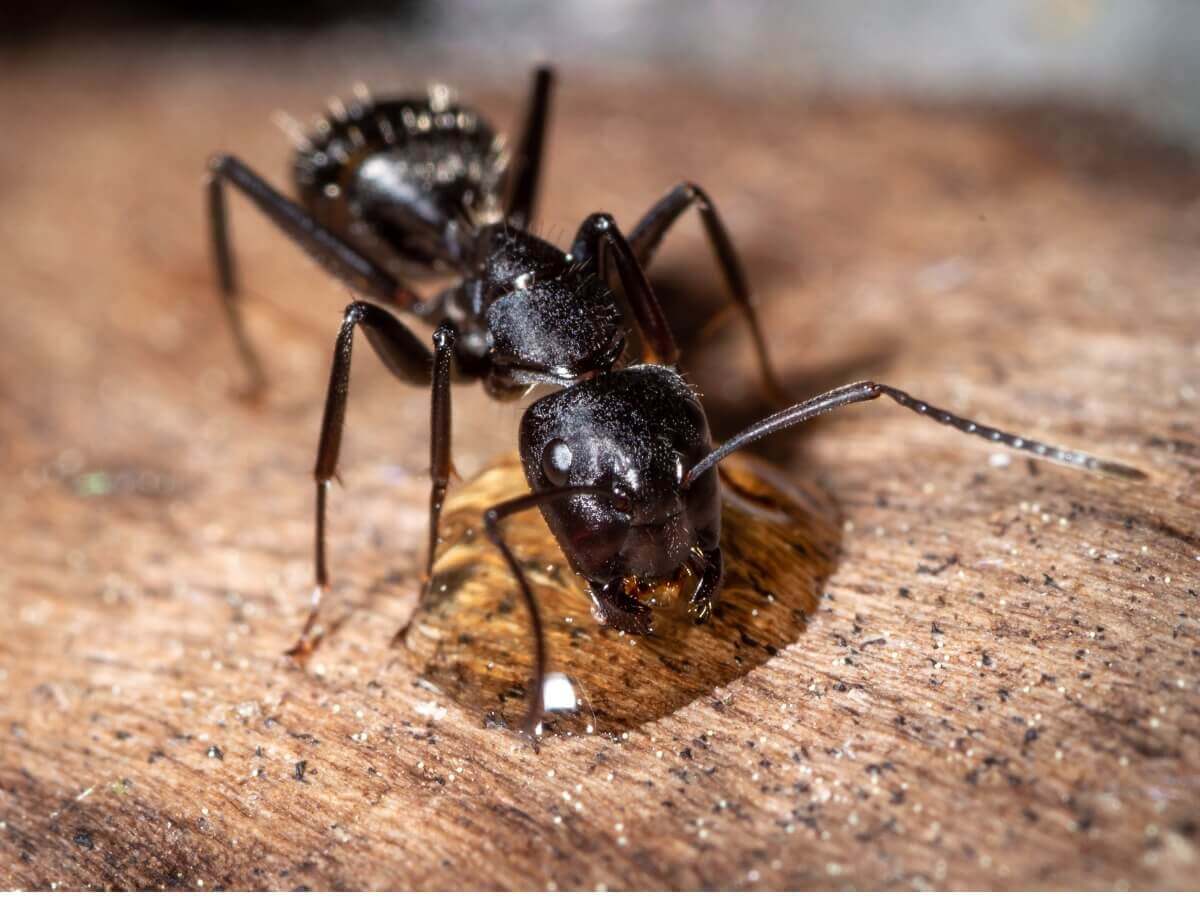

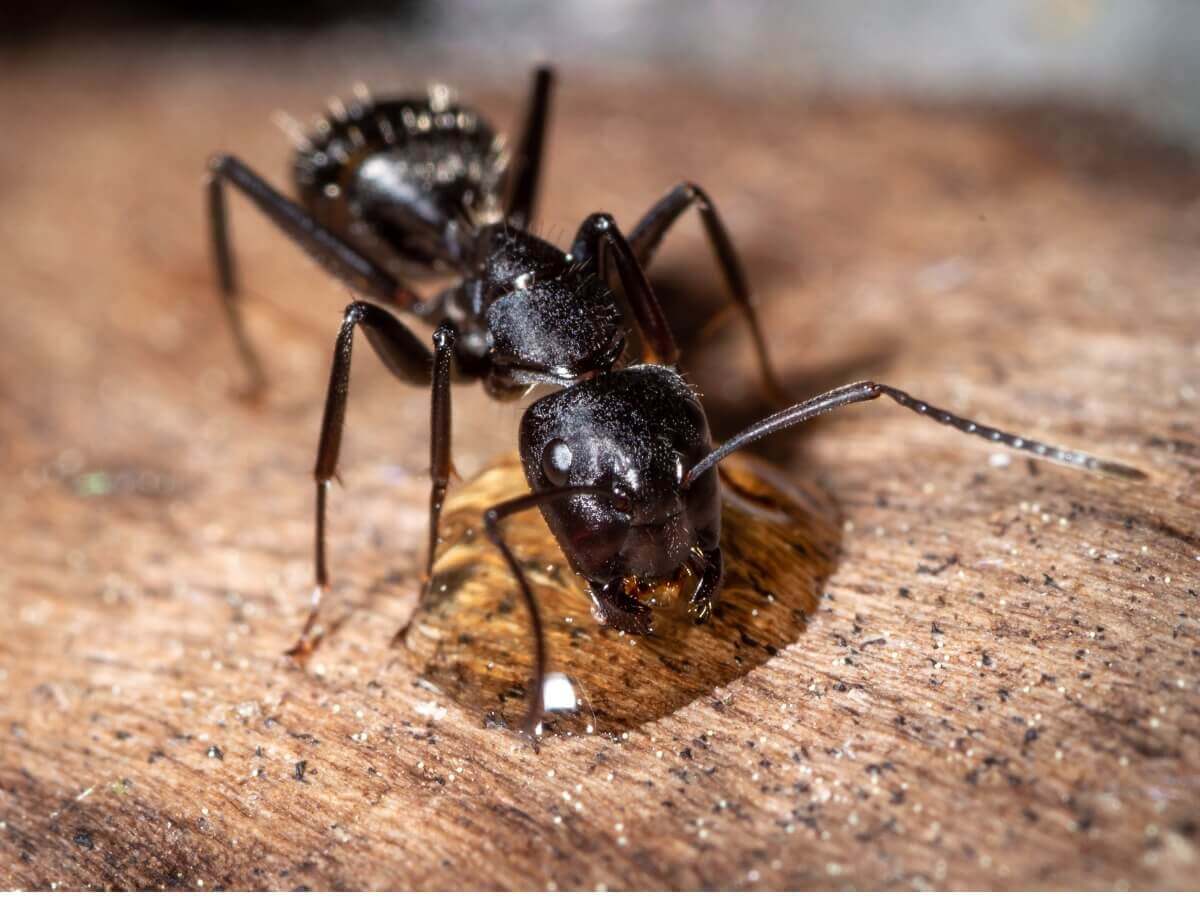

General characteristics of ants

Before telling you why there are ants with wings, we think it’s interesting to briefly explore their general characteristics. Ants represent a group of eusocial insects belonging to the family Formicidae and to the order Hymenoptera, that is, they’re close relatives of bees and wasps.

Like all insects, their body is divided into 3 sections or tagmae: A head with sensory organs such as compound eyes, ocelli, and antennae; a thorax with 3 pairs of legs (and wings in the case of reproductive specimens); and an abdomen, with the reproductive organs, respiratory tracheae, and excretory systems.

About 14 000 species of ants have been described, but it’s estimated that there may be more than 22 000 worldwide. They account for up to 25% of the terrestrial animal biomass and have colonized the entire surface of the planet, except for the Antarctic and some remote islands.

A caste system

Ants are eusocial (the highest degree of cooperation in the animal kingdom), which means that an anthill is a functional unit that’s much more than the sum of its parts. The colony is composed of thousands of individuals and is divided into the following castes:

- Queen: The queen is an ant that’s a product of sexual reproduction, so she’s a diploid (has a double number of chromosomes, half from the father and half from the mother). She’s the only one able to reproduce, and the whole colony revolves around her, as she’s the one in charge of laying the eggs. Queens can live for up to 10 years, some even 30.

- Workers: The queen is the center of the colony, but the workers are the ones who act and do all the work, from building galleries to feeding the larvae. Their life expectancy is between months and a year (2 at most) and there are thousands of them in each anthill. They’re also diploids because the eggs from which they hatch have been fertilized by the sperm stored by the queen.

- Males: Males come from asexual reproduction and are haploid (they have half chromosomes because their eggs haven’t been fertilized). They lack the functional biology of queens and workers, so they only live to reproduce and die within days of birth.

Why are there ants with wings?

As we’ve hinted in previous lines, the presence or absence of wings depends on the reproductive role of the specimen in the colony. Reproductive females are born in the anthill as winged princesses and take flight to the skies in order to be fertilized. The males are also winged. Workers and fertilized queens lack these structures.

When conditions are right (usually when temperatures drop after the summer and with it rains), thousands of princesses and males of the same species emerge synchronously from the nests in a biological event known as nuptial flight. During the flights, the princesses reproduce with more than 1 male and store the sperm in their spermatheca.

Once fertilized, the princess in question looks for a suitable place to establish her colony. She goes underground and tears off her wings, at which point she becomes the queen of a new colony. As the Royal Society indicates, the queen is able to store the sperm obtained in the nuptial flight for decades, so she can produce fertile eggs until she dies.

Most winged ants die

However, the whole process isn’t as pretty as it seems. As studies indicate, up to 45% of settled queens of many species (such as Acromyrmex subterraneus) die within days of burying underground. We must also factor in the mortality rate of ants with wings in general, as they’re food for birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates.

The vast majority of virgin princesses die within hours of leaving the nest without reproducing. Not only are they preyed upon by larger animals, but they’re also attacked by ants from other colonies (of the same or other species), drown, suffer from thermal shock, or become dehydrated. Of all the princesses produced in a colony, only 1 or 2 will come to establish a new anthill.

The nuptial flight of most ant species is massive, but the high mortality rate of winged ants (both princesses and males) means that only a small percentage of them result in new colonies.

Are ants with wings dangerous?

Ultimately, we want to stress the importance of not killing the ants with wings that you may encounter. They’re not mosquitoes, flies, or any type of insect that’s already reproduced, so it’s essential that you let them go on their way so that they can leave offspring. If you kill them, you further reduce the chances of new colonies being founded.

Whether male or female, winged ants don’t sting or bite. They’re only interested in reproducing and will die soon after if they don’t succeed.

As you can see, the presence of winged ants in the environment responds to a fascinating biological event. The nuptial flight shows us that even the most apparently simple animals keep impressive secrets regarding their reproductive behavior. If you observe a flight in your area, observe and document it, but intervene as little as possible.

Surely you’ve seen ants with wings, right? Strange as it may seem, this event isn’t a mistake of nature or an atypical occurrence, as it responds to the reproductive mechanism of the vast majority of social hymenopterans. The massive emergence of winged ants at ideal times when it comes to temperature and humidity is known as nuptial flight and is fascinating.

Ant colonies generally live underground or in decaying logs, but from time to time, some winged individuals must be born so that the dispersion of genes occurs beyond the anthill itself. If you want to know more about this topic, we encourage you to keep reading.

General characteristics of ants

Before telling you why there are ants with wings, we think it’s interesting to briefly explore their general characteristics. Ants represent a group of eusocial insects belonging to the family Formicidae and to the order Hymenoptera, that is, they’re close relatives of bees and wasps.

Like all insects, their body is divided into 3 sections or tagmae: A head with sensory organs such as compound eyes, ocelli, and antennae; a thorax with 3 pairs of legs (and wings in the case of reproductive specimens); and an abdomen, with the reproductive organs, respiratory tracheae, and excretory systems.

About 14 000 species of ants have been described, but it’s estimated that there may be more than 22 000 worldwide. They account for up to 25% of the terrestrial animal biomass and have colonized the entire surface of the planet, except for the Antarctic and some remote islands.

A caste system

Ants are eusocial (the highest degree of cooperation in the animal kingdom), which means that an anthill is a functional unit that’s much more than the sum of its parts. The colony is composed of thousands of individuals and is divided into the following castes:

- Queen: The queen is an ant that’s a product of sexual reproduction, so she’s a diploid (has a double number of chromosomes, half from the father and half from the mother). She’s the only one able to reproduce, and the whole colony revolves around her, as she’s the one in charge of laying the eggs. Queens can live for up to 10 years, some even 30.

- Workers: The queen is the center of the colony, but the workers are the ones who act and do all the work, from building galleries to feeding the larvae. Their life expectancy is between months and a year (2 at most) and there are thousands of them in each anthill. They’re also diploids because the eggs from which they hatch have been fertilized by the sperm stored by the queen.

- Males: Males come from asexual reproduction and are haploid (they have half chromosomes because their eggs haven’t been fertilized). They lack the functional biology of queens and workers, so they only live to reproduce and die within days of birth.

Why are there ants with wings?

As we’ve hinted in previous lines, the presence or absence of wings depends on the reproductive role of the specimen in the colony. Reproductive females are born in the anthill as winged princesses and take flight to the skies in order to be fertilized. The males are also winged. Workers and fertilized queens lack these structures.

When conditions are right (usually when temperatures drop after the summer and with it rains), thousands of princesses and males of the same species emerge synchronously from the nests in a biological event known as nuptial flight. During the flights, the princesses reproduce with more than 1 male and store the sperm in their spermatheca.

Once fertilized, the princess in question looks for a suitable place to establish her colony. She goes underground and tears off her wings, at which point she becomes the queen of a new colony. As the Royal Society indicates, the queen is able to store the sperm obtained in the nuptial flight for decades, so she can produce fertile eggs until she dies.

Most winged ants die

However, the whole process isn’t as pretty as it seems. As studies indicate, up to 45% of settled queens of many species (such as Acromyrmex subterraneus) die within days of burying underground. We must also factor in the mortality rate of ants with wings in general, as they’re food for birds, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates.

The vast majority of virgin princesses die within hours of leaving the nest without reproducing. Not only are they preyed upon by larger animals, but they’re also attacked by ants from other colonies (of the same or other species), drown, suffer from thermal shock, or become dehydrated. Of all the princesses produced in a colony, only 1 or 2 will come to establish a new anthill.

The nuptial flight of most ant species is massive, but the high mortality rate of winged ants (both princesses and males) means that only a small percentage of them result in new colonies.

Are ants with wings dangerous?

Ultimately, we want to stress the importance of not killing the ants with wings that you may encounter. They’re not mosquitoes, flies, or any type of insect that’s already reproduced, so it’s essential that you let them go on their way so that they can leave offspring. If you kill them, you further reduce the chances of new colonies being founded.

Whether male or female, winged ants don’t sting or bite. They’re only interested in reproducing and will die soon after if they don’t succeed.

As you can see, the presence of winged ants in the environment responds to a fascinating biological event. The nuptial flight shows us that even the most apparently simple animals keep impressive secrets regarding their reproductive behavior. If you observe a flight in your area, observe and document it, but intervene as little as possible.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Chérasse, S., & Aron, S. (2018). Impact of immune activation on stored sperm viability in ant queens. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1893), 20182248.

- Sales, T. A., Toledo, A. M. O., & Lopes, J. F. S. (2020). The best of heavy queens: influence of post-flight weight on queens’ survival and productivity in Acromyrmex subterraneus (Forel, 1893)(Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux, 67(3), 383-390.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.