Papillomas in Dogs: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments

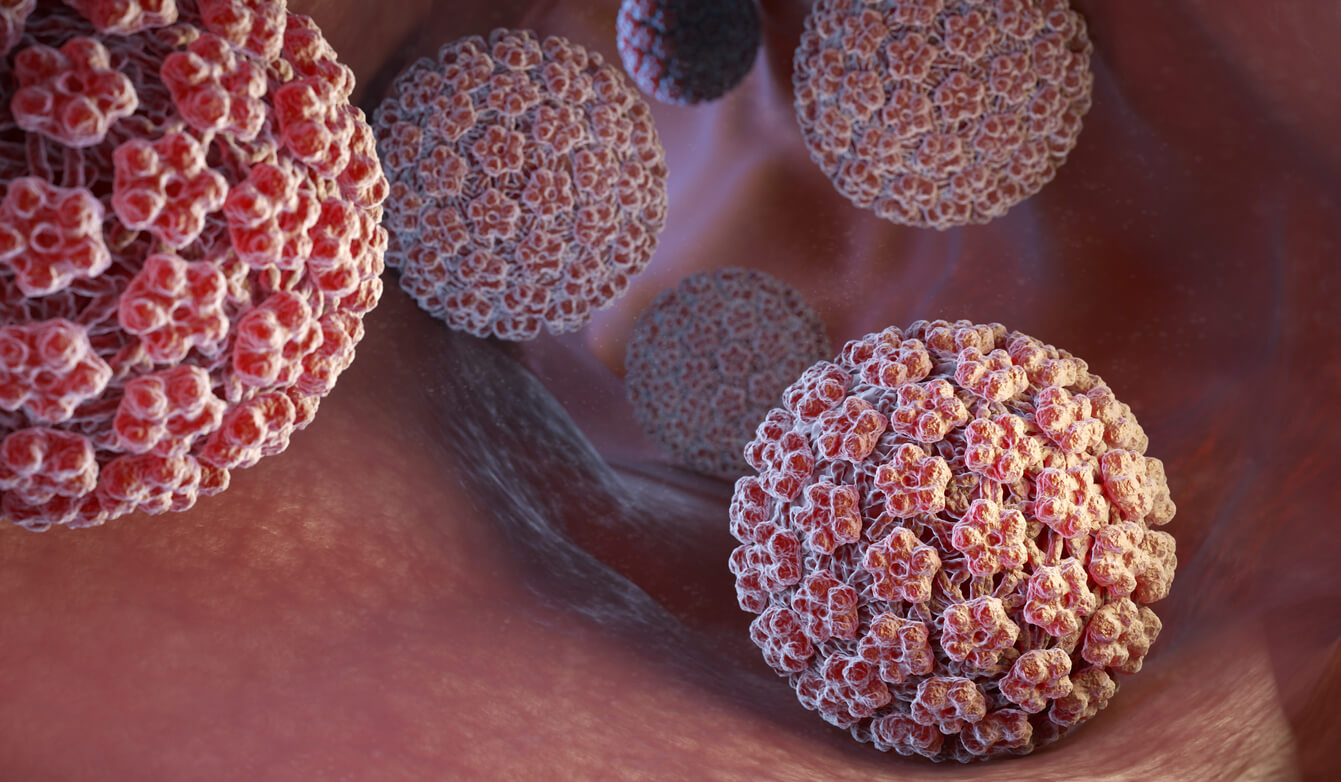

Papillomaviruses (Papillomaviridae) are a group of pathogenic viral agents that infect vertebrates. More than 100 different types have been isolated in humans alone, some of them anecdotal in nature and others causing cervical cancer in women (HPV-16 and HPV-18). Beyond our species, did you know that it’s possible to have papillomas in dogs too?

Indeed, papillomas in dogs are benign tumors caused by papillomavirus, although those that infect them aren’t the same as those that cause symptoms in humans. The different species of viruses in this group are very specific in terms of the replication mechanism, so they don’t usually “jump” between species.

What are papillomas in dogs?

The word papilloma may sound a bit technical, but if we use the term “wart” it’ll give you an idea as to what we’re talking about. Papillomas, in dogs and any other animal, are benign tumors caused by papillomaviruses, in this case, ones that are specialized in infecting canine cells.

The oral mucosa and the corners of the lips are the most common places where papillomas form, but they can also appear on the skin and even on the genitals, especially if the transmission has been through sexual contact with an infected animal. The nature of the virus usually determines where the infection occurs.

Characteristics of the virus

Papillomaviruses (PV) are DNA pathogens with about 8000 base pairs integrated into their genome, in turn covered by an accessory non-enveloped icosahedral capsid. As these viruses don’t have organelles and cellular structures, they must “hijack” the host’s cells and integrate themselves into them in order to multiply and spread among individuals.

The target of PV is epithelial cells, although only those with proliferative potential are invaded, as this is a requirement for the infection to be persistent. It should be noted that, once the viruses enter the dog’s body, an asymptomatic phase is established that lasts at least 4 weeks.

Types of canine papillomavirus

As we’ve said, in humans there are more than 100 types of papillomavirus, probably because in our species, it’s the one that has been studied the most. Although more than half of the PVs described come from infections in Homo sapiens, we can highlight the following variants in dogs:

- CPV1: Usually causes asymptomatic infections, although it’s also the cause of internalized or more external lesions – endophytic and exophytic, respectively.

- CPV2 – Causes endophytic and exophytic lesions, but it’s also the culprit for the development of invasive squamous cell carcinomas.

- Types CPV3, CPV4, CPV5: All 3 types cause the emergence of pigment plaques.

- CPV6: Causes endophytic papillomas.

- CPV 7: Causes exophytic papillomas.

Symptoms of papillomas in dogs

As indicated by the VCA Hospitals portal, papillomas in dogs can occur in different areas. In puppies and young dogs, clusters form on the oral mucosa and the corner of the lips. On the other hand, in dogs of all ages, they appear as single warts anywhere on the skin.

Some more specific types of PVs may appear in the genital area in clusters, while others appear on the eyelids or at the border of the tear duct. However, they all have one thing in common: they cause dry polyps (warts), scaly plaques, or hard structures that grow inwardly.

Depending on the size and location of the papillomas, they can be completely harmless or cause some symptoms. Among the possible clinical signs, we can highlight the following:

- Difficulty eating: This occurs in cases where many papillomas form on the palate, oropharynx, or corner of the lips.

- Bleeding: The dog may scratch a papilloma on its skin and cause it to bleed. Sometimes puppies bite the lumps that grow in their mouths when they eat and these also bleed.

- Pain: Those papillomas that grow “inward” can be painful, especially if they appear on the soles of one leg. In this case, the dog will limp and lick the area.

Some infections are completely asymptomatic. It all depends on the type of papillomavirus and the health status of the animal.

How does it spread?

As we said above, papillomas in dogs appear by contagion with some of the canine papillomavirus variants. However, the route of entry can be very different, depending on the pathogen and the animal’s general health.

These viruses are very resistant and can survive in an environment outside of their host. For this reason, the dog will become infected when it comes into direct contact with another infected dog, but also if it plays with infected objects or if it shares certain hygiene elements with other animals.

Papillomaviruses usually enter through the animal’s wounds, so fleas or ticks can help them.

Diagnosis of papillomas in dogs

Papillomas are very similar to each other, but can sometimes be confused with sebaceous tumors and other epidermal conditions. In order to obtain an accurate diagnosis, the veterinary clinic usually uses aspiration injection. With this technique, a group of cells from the lesion can be collected in a minimally invasive way and observed under a microscope.

In some cases, the sample obtained after injection isn’t sufficiently revealing. In this scenario, a complete resection of the wart is recommended, which is then analyzed on a laboratory basis. Thus, melanomas and more serious conditions are ruled out.

Treatment

The treatment of papillomas in dogs will depend on the location of the warts and the general health of the animal. For example, some of these formations are reabsorbed on their own in 1 or 2 months, as the animal’s immune system fights against the infection and kills it.

In cases where this doesn’t happen, direct surgical removal or removal by electrosurgery or radiosurgery can be used. In healthy specimens, the reappearance of a wart once the treatment has been carried out is very rare.

If the animal is immunosuppressed, more papillomas may appear on the body. In these cases, more specific treatments are required.

These aren’t a serious problem. Even though they remain on the animal’s skin for some time, if they don’t grow or spread, then there’s nothing to worry about. On the other hand, if a group of lesions is established in the oral mucosa of the dog, then a surgical intervention may be necessary, especially if they make swallowing or chewing difficult.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Papillomas of the skin, VCA Hospitals. Recogido a 20 de julio en https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/papilloma-of-the-skin

- Regalado Ibarra, A. M., Legendre, L., & Munday, J. S. (2018). Malignant transformation of a canine papillomavirus type 1-induced persistent oral papilloma in a 3-year-old dog. Journal of veterinary dentistry, 35(2), 79-95.

- Lane, H. E., Weese, J. S., & Stull, J. W. (2017). Canine oral papillomavirus outbreak at a dog daycare facility. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 58(7), 747.

- Orbell, H. L., Munday, J. S., Orbell, G. M., & Griffin, C. E. (2020). Development of multiple cutaneous and follicular neoplasms associated with canine papillomavirus type 3 in a dog. Veterinary Dermatology.

- Thaiwong, T., Sledge, D. G., Wise, A. G., Olstad, K., Maes, R. K., & Kiupel, M. (2018). Malignant transformation of canine oral papillomavirus (CPV1)-associated papillomas in dogs: An emerging concern?. Papillomavirus Research, 6, 83-89.