The Flower Hat Jelly: Is it Dangerous?

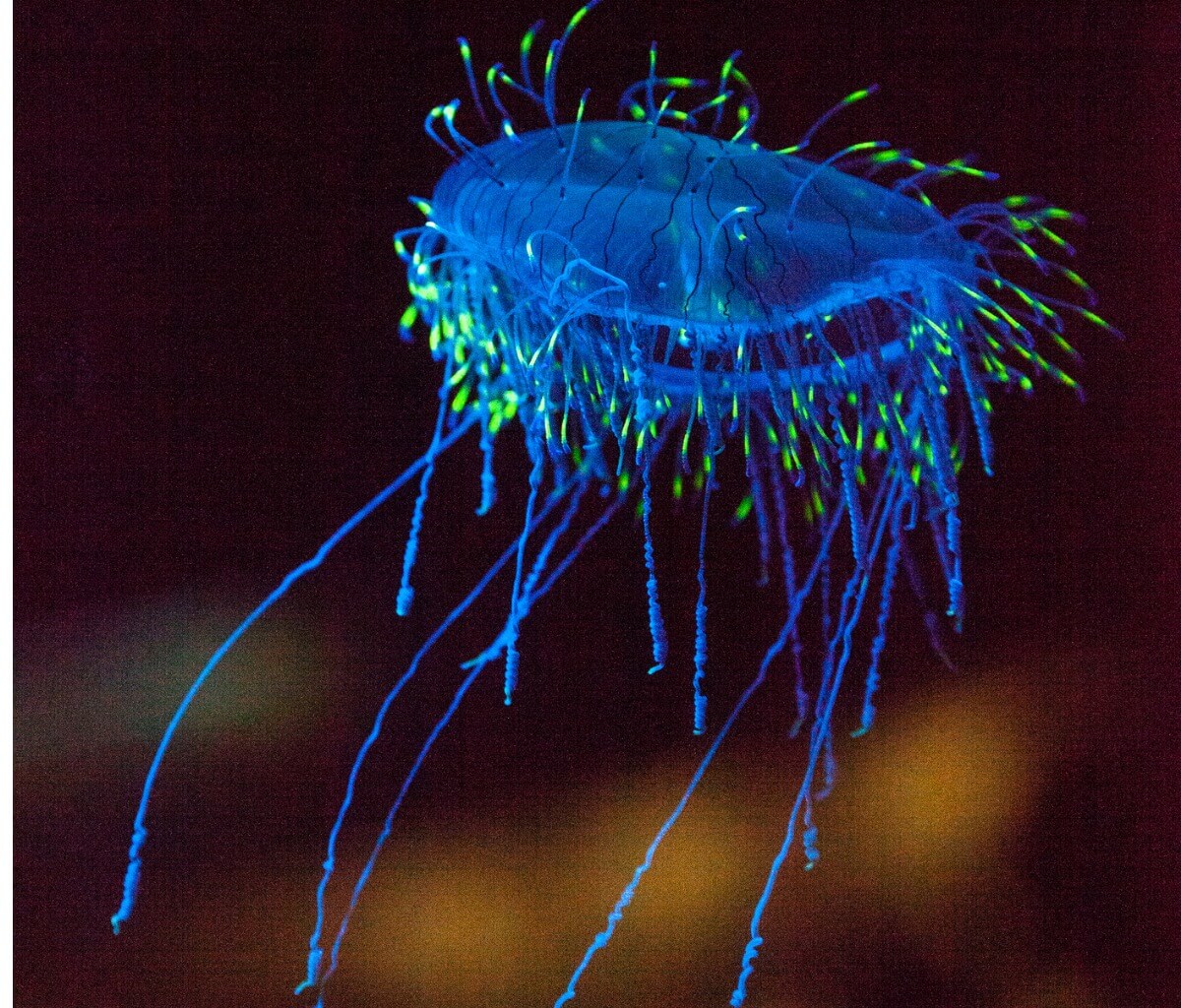

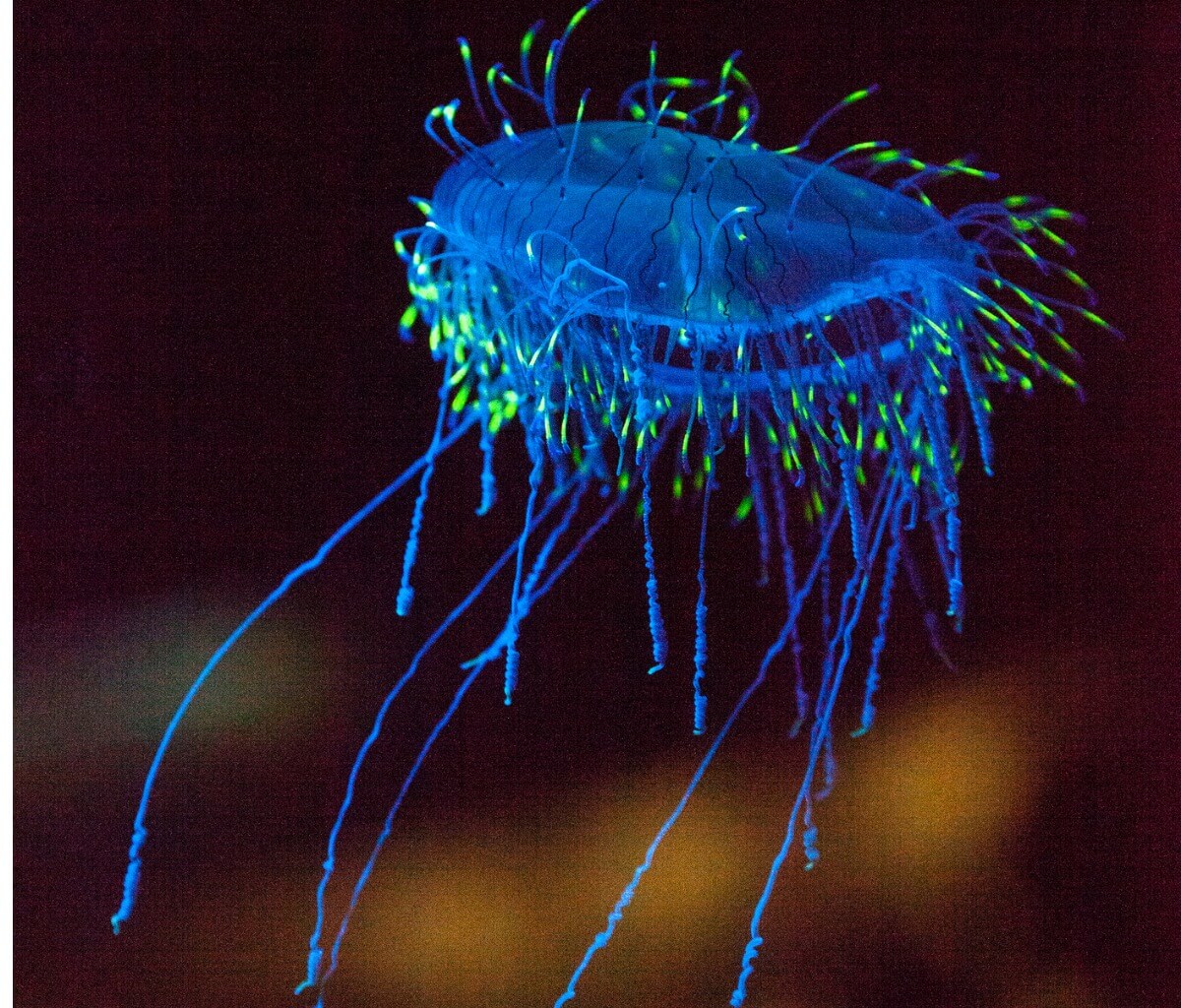

Cnidarians arouse mixed emotions in most of us. They look so mysterious and fascinating, but, at the same time, you don’t want to get too close! The flower hat jelly is no exception: its incredible looks inevitably attract the eye, but many wonder if it’s dangerous.

If you want to get to know more about this little swimming jelly, we’re going to tell you all about it today. With its neon tentacles and its alien shape, we’re sure you’ll be fascinated!

Characteristics of the flower hat jelly

In the first place, its true name is the flower hat jelly, not the flower hat jellyfish. It belongs in the class Hydrozoa, whereas true jellyfish belong to the class Scyphozoa. As a result, most experts consider that it isn’t really a true jellyfish.

The flower hat jelly (Olindias formosa) is an invertebrate of the cnidarians family that lives in the waters of Japan, Brazil and Argentina, usually in coastal areas where marine algae abound. They’re nocturnal animals, as they take advantage of the darkness of the night to hunt the small fish that inhabit the seabed.

These animals can measure up to 15 centimeters (6 inches) and their life expectancy is about 6 months. They have about 300 tentacles ending in a small bioluminescent bulge. Being nocturnal, studies claim that this light emission helps the jellyfish attract prey.

The reproduction of the flower hat jellyfish, a mystery

Jellies, just like jellyfish, reproduce alternately, like most cnidarians. This means that they alternate sexual and asexual reproduction to ensure a good number of offspring and genetic variability. However, until recently, the entire life cycle of this jellyfish wasn’t fully known, as it was impossible to breed it in captivity.

Cambridge University studies bring us the answer. Its maturation cycle is as follows:

- Adult jelly: This is through sexual reproduction, and it releases microscopic gametes and eggs into the surrounding water, where fertilization with the genetic material of other jellyfish occurs. The offspring produced in this interaction aren’t copies of their father or mother, but, rather, a combination of both.

- Planules or larvae, which hatch from the eggs and adhere to a hard surface.

- Polyps: Asexual reproduction occurs at this stage, as polyps proliferate and the juvenile jellies will be born from them. Interestingly, the polyps of the flower hat jelly have only one tentacle, albeit a very active one. The offspring produced at this stage will be genetically the same as its predecessor.

- Juvenile jellies: At this stage, the jelly will develop to its adult size – at this time it’s only about 2 millimeters long – thus closing the reproductive cycle.

Some curiosities about this jelly

The flower hat jelly has a unique adaptation: when food is scarce, it’s able to reduce its body size. In this way, the need for ingestion decreases, and its chances of survival increase.

Furthermore, this invertebrate doesn’t have a head, brain, heart, bones, cartilage, or eyes. Its body is made up almost entirely of water, to be exact, 95%. Its somatic sensitivity is carried out by cells specialized in detecting physical stimuli around it.

This jelly’s bioluminescence, produced by proteins present at the ends of its tentacles, is also observed in the polyp stage. In this period, the polyp uses its single tentacle to sweep its surroundings in search of nutrients, a process that also seems to be favored by the light it emits.

Flower hat jelly: is it dangerous?

If you’re concerned about running into one of these invertebrates, fear not, because it doesn’t have enough venom to kill you. Since it preys on small fish, its toxins are powerful enough to kill them almost instantly, but not enough for an adult human.

The sting is painful and looks like a burn. It can be treated by conventional methods: applying saline water and going to the aid station. The area shouldn’t be scratched or rubbed, otherwise the toxins will penetrate further into the skin.

Jellies and jellyfish eject their venom thanks to cnidocytes, specialized cells. These cell bodies have a “harpoon” that propels itself with direct contact, thus injecting toxins into the skin of the prey.

Conclusions: state of conservation and coexistence with humans

As it’s a rare species of jellyfish that inhabits small geographic areas, there are several conservation projects for the flower hat jelly. However, it isn’t considered to be in danger of extinction.

The biggest problems experienced by populations of humans living on the coasts where this jelly inhabits are stings – both for swimmers and divers. They have also been reported to obstruct fishing nets or water inlets in hydroelectric dams.

However, jellyfish fulfill their true role in nature in an effective way, controlling fish populations. In addition, its biofluorescence is being studied, in order to expand the knowledge about mimicry.

In short, the flower hat jelly is one more link in the delicate balance of the ecosystems it inhabits. Although it’s true that it can threaten certain economic activities, such as tourism or fishing, we must still ensure a positive coexistence with this, and all, the species that populate our planet.

Cnidarians arouse mixed emotions in most of us. They look so mysterious and fascinating, but, at the same time, you don’t want to get too close! The flower hat jelly is no exception: its incredible looks inevitably attract the eye, but many wonder if it’s dangerous.

If you want to get to know more about this little swimming jelly, we’re going to tell you all about it today. With its neon tentacles and its alien shape, we’re sure you’ll be fascinated!

Characteristics of the flower hat jelly

In the first place, its true name is the flower hat jelly, not the flower hat jellyfish. It belongs in the class Hydrozoa, whereas true jellyfish belong to the class Scyphozoa. As a result, most experts consider that it isn’t really a true jellyfish.

The flower hat jelly (Olindias formosa) is an invertebrate of the cnidarians family that lives in the waters of Japan, Brazil and Argentina, usually in coastal areas where marine algae abound. They’re nocturnal animals, as they take advantage of the darkness of the night to hunt the small fish that inhabit the seabed.

These animals can measure up to 15 centimeters (6 inches) and their life expectancy is about 6 months. They have about 300 tentacles ending in a small bioluminescent bulge. Being nocturnal, studies claim that this light emission helps the jellyfish attract prey.

The reproduction of the flower hat jellyfish, a mystery

Jellies, just like jellyfish, reproduce alternately, like most cnidarians. This means that they alternate sexual and asexual reproduction to ensure a good number of offspring and genetic variability. However, until recently, the entire life cycle of this jellyfish wasn’t fully known, as it was impossible to breed it in captivity.

Cambridge University studies bring us the answer. Its maturation cycle is as follows:

- Adult jelly: This is through sexual reproduction, and it releases microscopic gametes and eggs into the surrounding water, where fertilization with the genetic material of other jellyfish occurs. The offspring produced in this interaction aren’t copies of their father or mother, but, rather, a combination of both.

- Planules or larvae, which hatch from the eggs and adhere to a hard surface.

- Polyps: Asexual reproduction occurs at this stage, as polyps proliferate and the juvenile jellies will be born from them. Interestingly, the polyps of the flower hat jelly have only one tentacle, albeit a very active one. The offspring produced at this stage will be genetically the same as its predecessor.

- Juvenile jellies: At this stage, the jelly will develop to its adult size – at this time it’s only about 2 millimeters long – thus closing the reproductive cycle.

Some curiosities about this jelly

The flower hat jelly has a unique adaptation: when food is scarce, it’s able to reduce its body size. In this way, the need for ingestion decreases, and its chances of survival increase.

Furthermore, this invertebrate doesn’t have a head, brain, heart, bones, cartilage, or eyes. Its body is made up almost entirely of water, to be exact, 95%. Its somatic sensitivity is carried out by cells specialized in detecting physical stimuli around it.

This jelly’s bioluminescence, produced by proteins present at the ends of its tentacles, is also observed in the polyp stage. In this period, the polyp uses its single tentacle to sweep its surroundings in search of nutrients, a process that also seems to be favored by the light it emits.

Flower hat jelly: is it dangerous?

If you’re concerned about running into one of these invertebrates, fear not, because it doesn’t have enough venom to kill you. Since it preys on small fish, its toxins are powerful enough to kill them almost instantly, but not enough for an adult human.

The sting is painful and looks like a burn. It can be treated by conventional methods: applying saline water and going to the aid station. The area shouldn’t be scratched or rubbed, otherwise the toxins will penetrate further into the skin.

Jellies and jellyfish eject their venom thanks to cnidocytes, specialized cells. These cell bodies have a “harpoon” that propels itself with direct contact, thus injecting toxins into the skin of the prey.

Conclusions: state of conservation and coexistence with humans

As it’s a rare species of jellyfish that inhabits small geographic areas, there are several conservation projects for the flower hat jelly. However, it isn’t considered to be in danger of extinction.

The biggest problems experienced by populations of humans living on the coasts where this jelly inhabits are stings – both for swimmers and divers. They have also been reported to obstruct fishing nets or water inlets in hydroelectric dams.

However, jellyfish fulfill their true role in nature in an effective way, controlling fish populations. In addition, its biofluorescence is being studied, in order to expand the knowledge about mimicry.

In short, the flower hat jelly is one more link in the delicate balance of the ecosystems it inhabits. Although it’s true that it can threaten certain economic activities, such as tourism or fishing, we must still ensure a positive coexistence with this, and all, the species that populate our planet.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Olindias formosa. (2021). Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Olindias_formosa/

- Haddock, S. H., & Dunn, C. W. (2015). Fluorescent proteins function as a prey attractant: experimental evidence from the hydromedusa Olindias formosus and other marine organisms. Biology open, 4(9), 1094-1104.

-

Patry, W., Knowles, T., Christianson, LM y Howard, METRO. (2014). La etapa hidroide y medusa temprana de Olindias formosus (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Limnomedusae). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. Reino Unido 94, 1409-415. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025315414000691

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.