Jumping Spiders: Characteristics, Habitat, Diet, and Reproduction

Written and verified by the biologist Cesar Paul Gonzalez Gonzalez

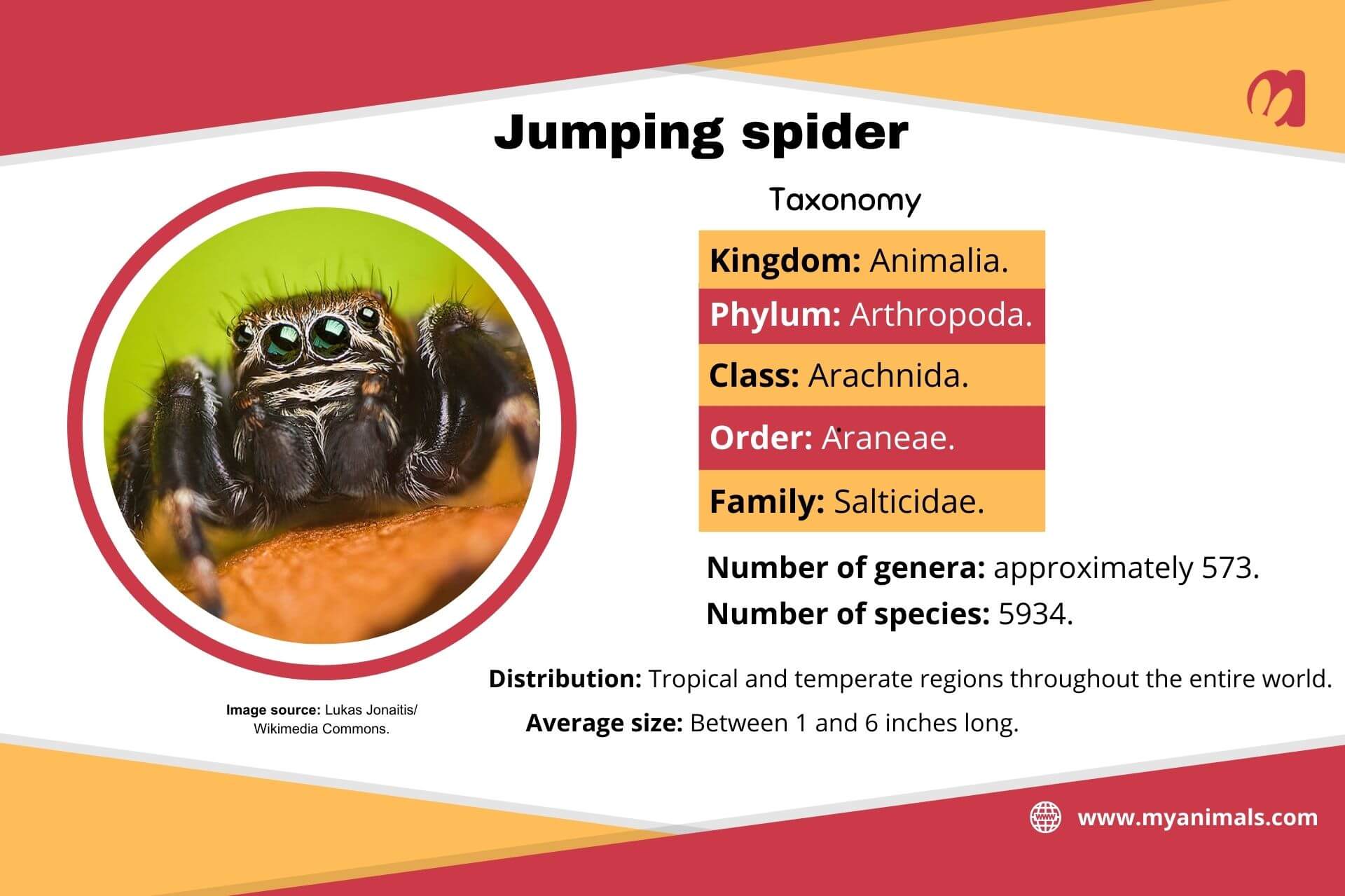

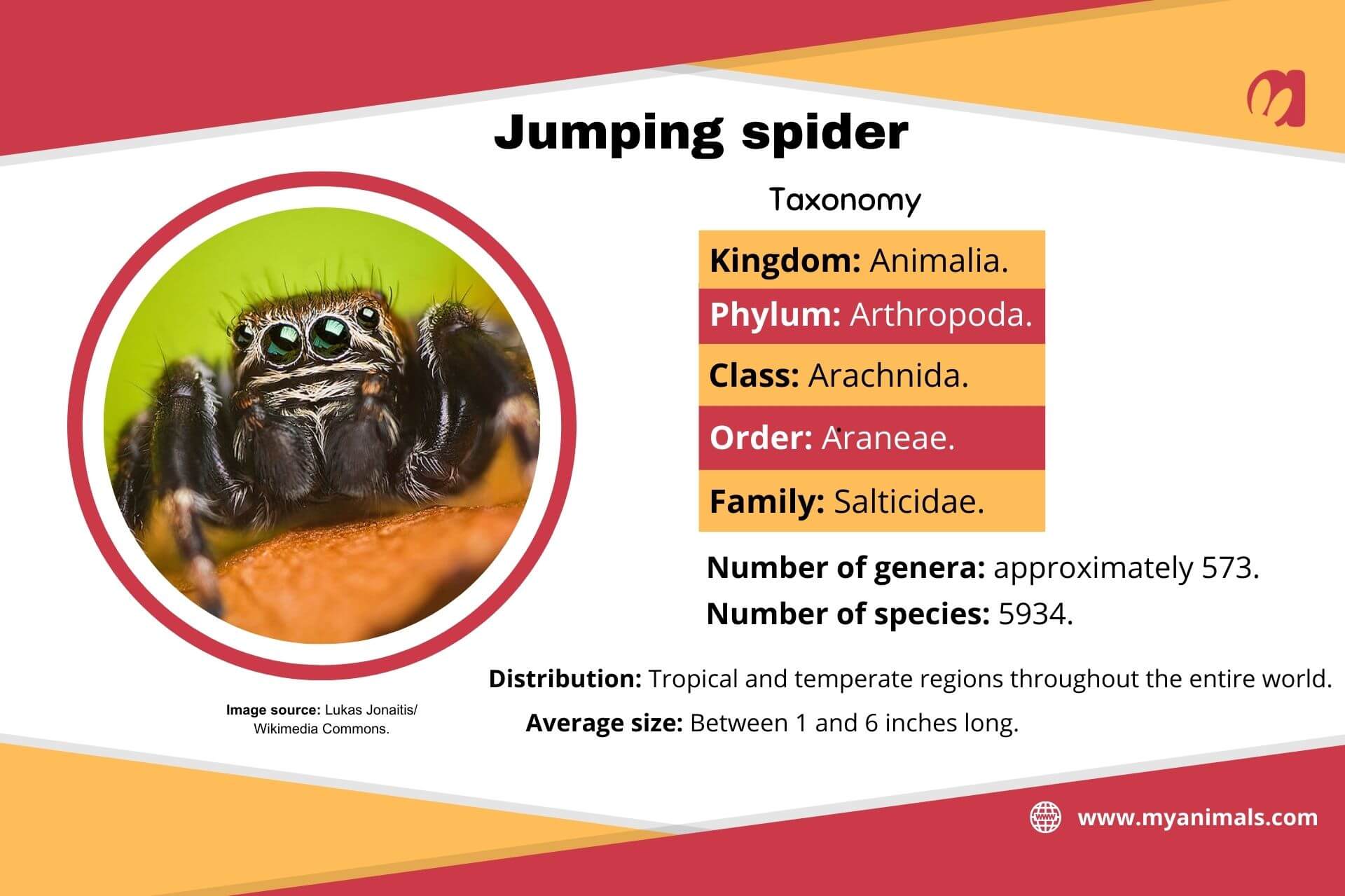

Jumping spiders have gained a lot of fame in recent years due to the fact that their “cute” appearance is one of the most striking in the world of arthropods. In fact, thanks to this, they have served as inspiration for several animated shorts, cartoons, and fictional stories.

Contrary to what you may think, the term “jumping spider” isn’t only used to name a single species, but also a whole taxonomic family. Do you want to discover more about these peculiar arachnids? Keep reading the following article.

Taxonomy of Salticidae

All jumping spiders are grouped in the family Salticidae (order Araneae), which is composed of 5,934 species and about 573 genres. However, according to an article published in Ecologica Montenegrina, about 2,204 species are yet to be fully described. That is, information is only available for one of the sexes (male or female).

As with other spider groups, there’s a lot of incomplete information on the genres and species that make up the salticid family. This is mainly due to the difficulty in finding them, as they’re small arachnids that are difficult to detect in nature.

Despite the lack of information, the family Salticidae represents one of the most diverse taxonomic groups in the world. In this regard, the book Salticid Spiders of Misiones: A Guide to Identification (basal tribes) states that such a wealth of species implies that it has a wide distribution. For this reason, jumping spiders have also become so popular around the world.

Where do jumping spiders live?

An article published in the journal Scientia states that jumping spiders have a wide distribution in tropical and temperate regions. However, they’re also capable of living in boreal zones, so temperature doesn’t seem to be a limiting factor for these species.

Jumping spiders are usually found in places with abundant vegetation, where they form deep associations with some types of plants.

They also live in microhabitats formed at different levels of height, from the treetops to the ground. This means that their location in nature will depend very much on the species involved.

What do jumping spiders look like?

Jumping spiders share the basic morphology of other arachnids. That is, their body is divided into two main sections:

- Prosoma: This is small and contains all appendages (limbs), mouth, and eyes.

- Opisthosoma: This is slightly larger and contains most of the spider’s organs.

It’s difficult to establish general characteristics that take into account each of the 5,934 species that exist. However, it’s possible to list the physical traits and qualities that are usually used to determine that a spider belongs to the family Salticidae. These are as follows:

- Small size: They measure between 0.11 and 0.59 inches in length (approximately).

- Large frontal eyes: Four of their eight eyes are frontal, and the two central ones stand out due to their size.

- Large pedipalps: The non-locomotive limbs (first pair) of these spiders often exhibit “unusual” width, which serves as a striking feature in the courtship process.

- Diagonally arranged chelicerae: These are two mouthparts that look like fangs and serve to trap prey.

- Display of trichobothria (hairs): The function and density of the hair may vary in each species, ranging from specimens with dense “hairs” to those in which this feature isn’t as evident.

- They don’t build webs to capture prey: Although jumping spiders have the ability to produce silk, they don’t use it as a hunting strategy. According to an article published in Current Biology, they tend to use their silk as a type of safety “rope” that “anchors” them to high surfaces in case they fall.

- Excellent locomotor ability: According to an article published in The Journal of Arachnology, the group of salticids – also known as jumping spiders – is known for its great speed when moving. This ability is often used during hunting and to escape from an enemy, often in combination with jumping.

You might be interested in: Amazing Facts About Spider Silk!

Colors

Although jumping spiders are known to have bright, eye-catching coloration, this characteristic isn’t always present in all species. In fact, a large portion of these arachnids exhibit the following color patterns, which are inconspicuous:

- Dark

- Opaque

- Translucent

In exceptional cases, certain species of jumping spiders use striking colors as a camouflage strategy.

For example, as reported in an article published in the Revista Brasileira de Biologia, the Psecas viridipurpureus sports a bright red body to go unnoticed on the leaves of Bromelia balansae.

Behavior

Contrary to other arachnids, salticids tend to be diurnal creatures that move about mostly during the day. According to an article published in Journal of Experimental Biology, such a “drastic” change seems to stem from their high visual capacity. This means that, as they can better perceive their environment thanks to their eyes, they prefer to carry out their activities under the sun’s illumination.

Of course, jumping spiders are also able to move at night, as their hair provides them with additional sensory information that complements their perception of the environment. Of course, there are certain limits to their nocturnal abilities, but they’re far from helpless.

What does a jumping spider eat?

Although dietary preference depends on each species of jumping spider, in general, they all feed on a wide variety of arthropods. According to an article published in the European Journal of Entomology, in the case of Menemerus taeniatus, the choice of prey seems to be limited by the size of the specimen.

That is, salticids tend to eat arthropods that are smaller than themselves.

These arachnids are excellent hunters. They stalk their prey for a few moments to confirm that it’s worth the effort and energy expenditure. As soon as they determine the payoff, they’re able to choose between different pursuit strategies. For example, some species sneak up on their victim and attack by surprise, while others decide to chase them (without stealth).

It should be noted that the diet of jumping spiders includes not only meat, but they can also consume plant nectar. Research reported through Cambridge University Press claims that at least 90 species of jumping spiders have been identified that occasionally feed on nectar.

The reproduction of jumping spiders

The courtship of jumping spiders is perhaps one of the most interesting events that can be perceived in the group. This is due to the fact that males use different movements and sounds to try to attract mates.

Although it’s not a general rule, most species initiate courtship by means of rhythmic movements in which they display their pedipalps.

These structures may or may not be decorated with colorful coloration patterns, which are highly visible during the process. In addition, colorful specimens such as the peacock spider (Maratus volans) often raise their abdomens to complement their “dances”.

This type of courtship allows males to get close enough to impregnate the female. Therefore, as soon as they come into contact, the male introduces the sperm packet (spermatophore) into the female and immediately moves away.

Female salticids place their eggs in silk sacks and store them in their shelters. Although there’s no obvious parental care as such, the mother protects her offspring and waits for her young to mature before leaving the nest.

Also read: Smiling Spiders: Behavior and Habitat

Small and peculiar

As you can see, salticids are interesting and diverse species that harbor endless curiosities. Of course, it’s impossible to address the peculiarities of every jumping spider, but it’s more than obvious that they have great charisma and presence in the world.

Jumping spiders have gained a lot of fame in recent years due to the fact that their “cute” appearance is one of the most striking in the world of arthropods. In fact, thanks to this, they have served as inspiration for several animated shorts, cartoons, and fictional stories.

Contrary to what you may think, the term “jumping spider” isn’t only used to name a single species, but also a whole taxonomic family. Do you want to discover more about these peculiar arachnids? Keep reading the following article.

Taxonomy of Salticidae

All jumping spiders are grouped in the family Salticidae (order Araneae), which is composed of 5,934 species and about 573 genres. However, according to an article published in Ecologica Montenegrina, about 2,204 species are yet to be fully described. That is, information is only available for one of the sexes (male or female).

As with other spider groups, there’s a lot of incomplete information on the genres and species that make up the salticid family. This is mainly due to the difficulty in finding them, as they’re small arachnids that are difficult to detect in nature.

Despite the lack of information, the family Salticidae represents one of the most diverse taxonomic groups in the world. In this regard, the book Salticid Spiders of Misiones: A Guide to Identification (basal tribes) states that such a wealth of species implies that it has a wide distribution. For this reason, jumping spiders have also become so popular around the world.

Where do jumping spiders live?

An article published in the journal Scientia states that jumping spiders have a wide distribution in tropical and temperate regions. However, they’re also capable of living in boreal zones, so temperature doesn’t seem to be a limiting factor for these species.

Jumping spiders are usually found in places with abundant vegetation, where they form deep associations with some types of plants.

They also live in microhabitats formed at different levels of height, from the treetops to the ground. This means that their location in nature will depend very much on the species involved.

What do jumping spiders look like?

Jumping spiders share the basic morphology of other arachnids. That is, their body is divided into two main sections:

- Prosoma: This is small and contains all appendages (limbs), mouth, and eyes.

- Opisthosoma: This is slightly larger and contains most of the spider’s organs.

It’s difficult to establish general characteristics that take into account each of the 5,934 species that exist. However, it’s possible to list the physical traits and qualities that are usually used to determine that a spider belongs to the family Salticidae. These are as follows:

- Small size: They measure between 0.11 and 0.59 inches in length (approximately).

- Large frontal eyes: Four of their eight eyes are frontal, and the two central ones stand out due to their size.

- Large pedipalps: The non-locomotive limbs (first pair) of these spiders often exhibit “unusual” width, which serves as a striking feature in the courtship process.

- Diagonally arranged chelicerae: These are two mouthparts that look like fangs and serve to trap prey.

- Display of trichobothria (hairs): The function and density of the hair may vary in each species, ranging from specimens with dense “hairs” to those in which this feature isn’t as evident.

- They don’t build webs to capture prey: Although jumping spiders have the ability to produce silk, they don’t use it as a hunting strategy. According to an article published in Current Biology, they tend to use their silk as a type of safety “rope” that “anchors” them to high surfaces in case they fall.

- Excellent locomotor ability: According to an article published in The Journal of Arachnology, the group of salticids – also known as jumping spiders – is known for its great speed when moving. This ability is often used during hunting and to escape from an enemy, often in combination with jumping.

You might be interested in: Amazing Facts About Spider Silk!

Colors

Although jumping spiders are known to have bright, eye-catching coloration, this characteristic isn’t always present in all species. In fact, a large portion of these arachnids exhibit the following color patterns, which are inconspicuous:

- Dark

- Opaque

- Translucent

In exceptional cases, certain species of jumping spiders use striking colors as a camouflage strategy.

For example, as reported in an article published in the Revista Brasileira de Biologia, the Psecas viridipurpureus sports a bright red body to go unnoticed on the leaves of Bromelia balansae.

Behavior

Contrary to other arachnids, salticids tend to be diurnal creatures that move about mostly during the day. According to an article published in Journal of Experimental Biology, such a “drastic” change seems to stem from their high visual capacity. This means that, as they can better perceive their environment thanks to their eyes, they prefer to carry out their activities under the sun’s illumination.

Of course, jumping spiders are also able to move at night, as their hair provides them with additional sensory information that complements their perception of the environment. Of course, there are certain limits to their nocturnal abilities, but they’re far from helpless.

What does a jumping spider eat?

Although dietary preference depends on each species of jumping spider, in general, they all feed on a wide variety of arthropods. According to an article published in the European Journal of Entomology, in the case of Menemerus taeniatus, the choice of prey seems to be limited by the size of the specimen.

That is, salticids tend to eat arthropods that are smaller than themselves.

These arachnids are excellent hunters. They stalk their prey for a few moments to confirm that it’s worth the effort and energy expenditure. As soon as they determine the payoff, they’re able to choose between different pursuit strategies. For example, some species sneak up on their victim and attack by surprise, while others decide to chase them (without stealth).

It should be noted that the diet of jumping spiders includes not only meat, but they can also consume plant nectar. Research reported through Cambridge University Press claims that at least 90 species of jumping spiders have been identified that occasionally feed on nectar.

The reproduction of jumping spiders

The courtship of jumping spiders is perhaps one of the most interesting events that can be perceived in the group. This is due to the fact that males use different movements and sounds to try to attract mates.

Although it’s not a general rule, most species initiate courtship by means of rhythmic movements in which they display their pedipalps.

These structures may or may not be decorated with colorful coloration patterns, which are highly visible during the process. In addition, colorful specimens such as the peacock spider (Maratus volans) often raise their abdomens to complement their “dances”.

This type of courtship allows males to get close enough to impregnate the female. Therefore, as soon as they come into contact, the male introduces the sperm packet (spermatophore) into the female and immediately moves away.

Female salticids place their eggs in silk sacks and store them in their shelters. Although there’s no obvious parental care as such, the mother protects her offspring and waits for her young to mature before leaving the nest.

Also read: Smiling Spiders: Behavior and Habitat

Small and peculiar

As you can see, salticids are interesting and diverse species that harbor endless curiosities. Of course, it’s impossible to address the peculiarities of every jumping spider, but it’s more than obvious that they have great charisma and presence in the world.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Arizala, S. & Quintero, D. (2016). Diversidad de arañas saltarinas (Araneae: Salticidae) en dos Especies de Bromelias (Poales: Bromeliaceae) del Parque Nacional Altos de Campana, Panamá. Scientia, 26(1), 25-36. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308202192_Diversidad_de_aranas_saltarinas_Araneae_Salticidae_en_dos_especies_de_bromeli

- Bartos, M., & Szczepko, K. (2012). Development of prey-specific predatory behavior in a jumping spider (Araneae: Salticidae). The Journal of Arachnology, 40(2), 228-233. https://bioone.org/journals/the-journal-of-arachnology/volume-40/issue-2/Hi11-66.1/Development-of-prey-specific-predatory-behavior-in-a-jumping-spider/10.1636/Hi11-66.1.short

- Cerveira, A. M., Jackson, R. R., & Nelson, X. J. (2019). Dim-light vision in jumping spiders (Araneae, Salticidae): identification of prey and rivals. Journal of Experimental Biology, 222(9), jeb198069. https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/222/9/jeb198069/679/Dim-light-vision-in-jumping-spiders-Araneae

- Chen, A., Kim, K., & Shamble, P. S. (2021). Rapid mid-jump production of high-performance silk by jumping spiders. Current Biology, 31(21), R1422-R1423. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982221012938

- De Omena, P. M., & Romero, G. Q. (2010). Using visual cues of microhabitat traits to find home: the case study of a bromeliad-living jumping spider (Salticidae). Behavioral Ecology, 21(4), 690-695. https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/21/4/690/247649

- Huseynov, E. F. (2005). Natural prey of the jumping spider Menemerus taeniatus (Araneae: Salticidae). European Journal of Entomology, 102(4), 797. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270497182_Natural_prey_of_the_jumping_spider_Menemerus_taeniatus_Araneae_Salticidae

- Jackson, R. R., Pollard, S. D., Li, D., & Fijn, N. (2002). Interpopulation variation in the risk-related decisions of Portia labiata, an araneophagic jumping spider (Araneae, Salticidae), during predatory sequences with spitting spiders. Animal Cognition, 5(4), 215. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12461599/

- Jackson, R. R., Pollard, S. D., Nelson, X. J., Edwards, G. B., & Barrion, A. T. (2001). Jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) that feed on nectar. Journal of Zoology, 255(1), 25-29. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-zoology/article/abs/jumping-spiders-araneae-salticidae-that-feed-on-nectar/7690330E37C061FA101EEACAAA76F890

- Maddison, W. P. (2015). A phylogenetic classification of jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae). Journal of Arachnology, 231-292. https://bioone.org/journals/the-journal-of-arachnology/volume-43/issue-3/arac-43-03-231-292/A-phylogenetic-classification-of-jumping-spiders-Araneae-Salticidae/10.1636/arac-43-03-231-292.short#:~:text=The%20classification%20of%20jumping%20spiders,both%20molecular%20and%20morphological%20information.

- Maddison, W. P., & Hedin, M. C. (2003). Jumping spider phylogeny (Araneae: Salticidae). Invertebrate Systematics, 17(4), 529-549. https://www.publish.csiro.au/is/IS02044

- Maddison, W. P., Beattie, I., Marathe, K., Ng, P. Y., Kanesharatnam, N., Benjamin, S. P., & Kunte, K. (2020). A phylogenetic and taxonomic review of baviine jumping spiders (Araneae, Salticidae, Baviini). ZooKeys, 1004, 27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7758311/

- Prószyński, J. (2017). Pragmatic classification of the World’s Salticidae (Araneae). Ecologica Montenegrina, 12, 1-133. https://www.biotaxa.org/em/article/view/em.2017.12.1

- Richman, D. B., & Jackson, R. R. (1992). A review of the ethology of jumping spiders (Araneae, Salticidae). Bulletin of the British Arachnological Society, 9(2), 33-37. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267938733_A_review_of_the_ethology_of_jumping_spiders_Araneae_Salticidae

- Rossa-Feres, D. D. C., Romero, G. Q., Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E., & Feres, R. J. F. (2000). Reproductive behavior and seasonal occurrence of Psecas viridipurpureus (Salticidae, Araneae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia, 60, 221-228. https://www.scielo.br/j/rbbio/a/jDTHYD8WZLskPV3TfxzdZxf/?lang=en&format=html

- Rubio, G. D., Baigorria, J. E. M., & Scioscia, C. L. (2018). Arañas Saltícidas de Misiones: Guía para la Identificación (Tribus Basales). Universidad Maimónides. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/109420

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.