Is the Praying Mantis Poisonous?

Written and verified by the biologist Samuel Sanchez

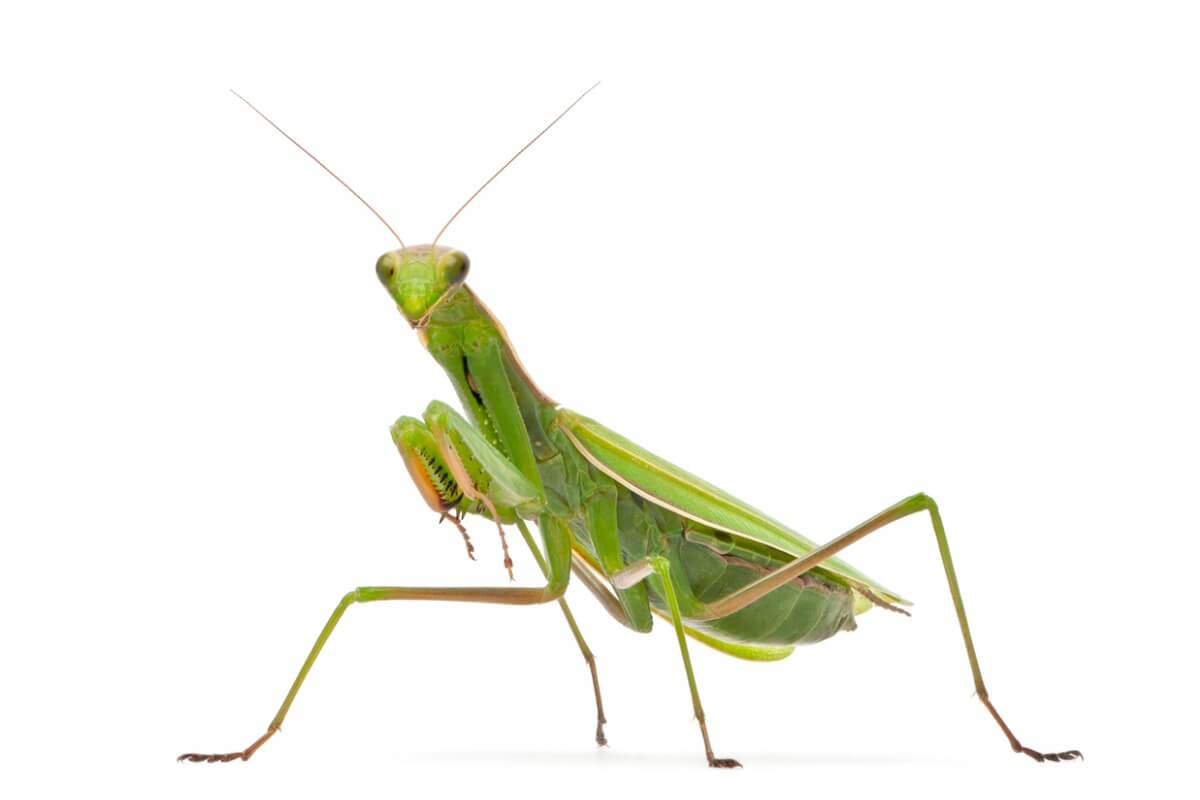

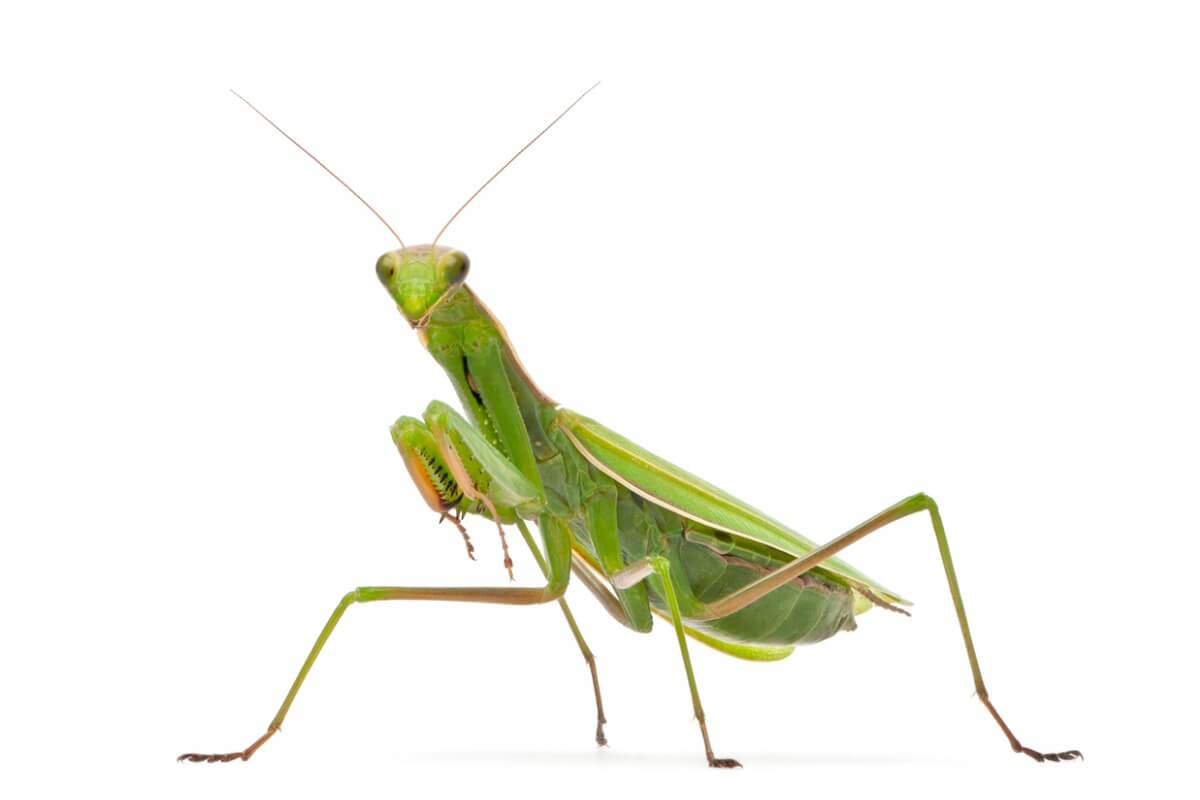

The praying mantis is an alien-looking creature that has prompted legends and fascination in equal parts. Its enlarged eyes, movable head, and hooked front legs always demand a reaction. It has adapted to hunting in so many ways, but is the praying mantis poisonous?

In this article, we’ll take a look at the defense techniques of this curious insect, which is much less dangerous than its appearance suggests. Do you want to know about the praying mantis and its relatives? Keep reading!

What are praying mantises?

Before answering the question that concerns us here, we think it would be good to talk about what mantises are, along with some of their general characteristics. These curious invertebrates are insects (class Insecta) belonging to the order Mantodea, which includes about 2400 species in 460 different genera.

There are mantids of all colors and sizes, but they all share a number of features typical of other insects: a head with a mandible, compound eyes, 3 simple eyes and antennae; a thorax with 3 pairs of legs and 2 pairs of wings; and a relatively thick abdomen, which houses the digestive and reproductive organs.

Praying mantises are very striking because they have a first pair of limbs “bent” in the shape of a hook, which gives them a constant praying appearance (hence their common name). However, they’re also characterized by their vertiginous reproductive process, their visual stereopsis, their ability to rotate their head 180°, and much more.

There are thousands of mantis species, among which the following stand out:

- Orchid mantis (Hymenopus coronatus): This is native to Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, and Sumatra. It’s characterized by its white and pink coloration and its atypical morphology, with which it tries to camouflage itself on the petals of different plant species. Females are much larger than males.

- Devil’s flower mantis (Idolomantis diabolica): Adult specimens are striking due to their large size, which ranges from 13 centimeters (5 inches) for females and 10 centimeters (4 inches) for males. It’s native to Kenya, Malawi, Ethiopia, Somalia, and other regions of Africa.

- Praying mantis (Mantis religiosa): Perhaps the best-known mantid species worldwide. It’s distributed throughout the old world (Eurasia) and has a rather simple greenish or straw coloration.

We could go on citing mantis species and fill an entire book, as there are more than 2000 of them and all of them are fascinating. However, we would like to focus our attention on the praying mantis species, as this is the one that may have made you ask the question in the headline of this article. Let’s get to it!

Is the praying mantis poisonous?

The answer to the question is simple and straightforward: no, not at all. No species of mantis synthesizes potent toxins in specific glands and, moreover, none of them have modified organs (such as stingers, fangs, or chelicerae) to inject them. In other words, they’re neither toxic (they don’t synthesize toxic compounds) nor poisonous (they can’t inject them).

The belief that the praying mantis is poisonous most likely arose from its appearance and behavior. It’s an animal with an alien morphology and has an excellent predatory capacity. How does it achieve this without inoculating its prey with toxins? Here’s how.

Praying mantis hunting

Mantids are generalist carnivores, i.e. they feed on any animal smaller than themselves that passes in front of them. Species that live in the upper sections of plants tend to prefer flying prey (flies and moths), while the larger and heavier ones may even catch geckos and small rodents sporadically.

The limbs play an essential role in this whole process. The praying mantis has a first pair of legs of a raptorial nature, in which the coxa and trochanter are fused to create a conspicuous base. The femur is the most powerful and visible segment and contains a series of internal “spikes” that help it to grasp its prey. Finally, the tibia represents the tip of the claw and is highly serrated.

Thanks to the shape of their limbs, mantids need only rely on their speed, vision, and camouflaging abilities to ambush and hunt prey. Once they have them between their raptorial legs, it’s very difficult for them to escape.

Mantids don’t need venom. Their legs are powerful enough to hold the prey securely in place while it’s eaten alive.

What to do if I’m bitten by a mantis?

The praying mantis (as well as all mantids) doesn’t have venom, but it does have jaws capable of tearing apart flesh and insect carcasses. One of these specimens will never attack you on its own, but it’s possible that by handling it inappropriately you may get a bite.

Although these insects aren’t poisonous, certain protocols must be taken into account to disinfect the wound in case of a bite.

- Wet your hands with warm water.

- Apply soap to your hands (either in gel or bar form) and rub them over the wound.

- Wash the affected area for at least 20 seconds. Be sure to sanitize the entire bite site and adjacent structures.

- Remove all the soap and dry the affected area.

- If you’re bleeding, apply a dressing or cotton to facilitate clotting and put on a band-aid.

Most mantids give a bite equivalent to a scratch, but larger species (some of the genus Hierodula) can break human skin and cause minor bleeding. As you can imagine, it’s always best to admire them from a distance to avoid mishaps.

After reading this article, you now know that the praying mantis isn’t poisonous; neither it nor any other species belonging to the order Mantodea. However, these insects aren’t short on “tools” and their powerful limbs are enough to keep the prey immobile while it’s devoured alive.

The praying mantis is an alien-looking creature that has prompted legends and fascination in equal parts. Its enlarged eyes, movable head, and hooked front legs always demand a reaction. It has adapted to hunting in so many ways, but is the praying mantis poisonous?

In this article, we’ll take a look at the defense techniques of this curious insect, which is much less dangerous than its appearance suggests. Do you want to know about the praying mantis and its relatives? Keep reading!

What are praying mantises?

Before answering the question that concerns us here, we think it would be good to talk about what mantises are, along with some of their general characteristics. These curious invertebrates are insects (class Insecta) belonging to the order Mantodea, which includes about 2400 species in 460 different genera.

There are mantids of all colors and sizes, but they all share a number of features typical of other insects: a head with a mandible, compound eyes, 3 simple eyes and antennae; a thorax with 3 pairs of legs and 2 pairs of wings; and a relatively thick abdomen, which houses the digestive and reproductive organs.

Praying mantises are very striking because they have a first pair of limbs “bent” in the shape of a hook, which gives them a constant praying appearance (hence their common name). However, they’re also characterized by their vertiginous reproductive process, their visual stereopsis, their ability to rotate their head 180°, and much more.

There are thousands of mantis species, among which the following stand out:

- Orchid mantis (Hymenopus coronatus): This is native to Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, and Sumatra. It’s characterized by its white and pink coloration and its atypical morphology, with which it tries to camouflage itself on the petals of different plant species. Females are much larger than males.

- Devil’s flower mantis (Idolomantis diabolica): Adult specimens are striking due to their large size, which ranges from 13 centimeters (5 inches) for females and 10 centimeters (4 inches) for males. It’s native to Kenya, Malawi, Ethiopia, Somalia, and other regions of Africa.

- Praying mantis (Mantis religiosa): Perhaps the best-known mantid species worldwide. It’s distributed throughout the old world (Eurasia) and has a rather simple greenish or straw coloration.

We could go on citing mantis species and fill an entire book, as there are more than 2000 of them and all of them are fascinating. However, we would like to focus our attention on the praying mantis species, as this is the one that may have made you ask the question in the headline of this article. Let’s get to it!

Is the praying mantis poisonous?

The answer to the question is simple and straightforward: no, not at all. No species of mantis synthesizes potent toxins in specific glands and, moreover, none of them have modified organs (such as stingers, fangs, or chelicerae) to inject them. In other words, they’re neither toxic (they don’t synthesize toxic compounds) nor poisonous (they can’t inject them).

The belief that the praying mantis is poisonous most likely arose from its appearance and behavior. It’s an animal with an alien morphology and has an excellent predatory capacity. How does it achieve this without inoculating its prey with toxins? Here’s how.

Praying mantis hunting

Mantids are generalist carnivores, i.e. they feed on any animal smaller than themselves that passes in front of them. Species that live in the upper sections of plants tend to prefer flying prey (flies and moths), while the larger and heavier ones may even catch geckos and small rodents sporadically.

The limbs play an essential role in this whole process. The praying mantis has a first pair of legs of a raptorial nature, in which the coxa and trochanter are fused to create a conspicuous base. The femur is the most powerful and visible segment and contains a series of internal “spikes” that help it to grasp its prey. Finally, the tibia represents the tip of the claw and is highly serrated.

Thanks to the shape of their limbs, mantids need only rely on their speed, vision, and camouflaging abilities to ambush and hunt prey. Once they have them between their raptorial legs, it’s very difficult for them to escape.

Mantids don’t need venom. Their legs are powerful enough to hold the prey securely in place while it’s eaten alive.

What to do if I’m bitten by a mantis?

The praying mantis (as well as all mantids) doesn’t have venom, but it does have jaws capable of tearing apart flesh and insect carcasses. One of these specimens will never attack you on its own, but it’s possible that by handling it inappropriately you may get a bite.

Although these insects aren’t poisonous, certain protocols must be taken into account to disinfect the wound in case of a bite.

- Wet your hands with warm water.

- Apply soap to your hands (either in gel or bar form) and rub them over the wound.

- Wash the affected area for at least 20 seconds. Be sure to sanitize the entire bite site and adjacent structures.

- Remove all the soap and dry the affected area.

- If you’re bleeding, apply a dressing or cotton to facilitate clotting and put on a band-aid.

Most mantids give a bite equivalent to a scratch, but larger species (some of the genus Hierodula) can break human skin and cause minor bleeding. As you can imagine, it’s always best to admire them from a distance to avoid mishaps.

After reading this article, you now know that the praying mantis isn’t poisonous; neither it nor any other species belonging to the order Mantodea. However, these insects aren’t short on “tools” and their powerful limbs are enough to keep the prey immobile while it’s devoured alive.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Brannoch, S. K., Wieland, F., Rivera, J., Klass, K. D., Olivier Béthoux, & Svenson, G. J. (2017). Manual of praying mantis morphology, nomenclature, and practices (Insecta, Mantodea). ZooKeys, (696), 1–100. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5673847/

- Mebs, D., Wunder, C., Pogoda, W., & Toennes, S. W. (2017). Feeding on toxic prey. The praying mantis (Mantodea) as predator of poisonous butterfly and moth (Lepidoptera) caterpillars. Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology, 131, 16–19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28300580/

- Nyffeler, M., Maxwell, M., & Remsen, J. (2017). Bird predation by praying mantises: a global perspective. The Wilson Journal of Ornitology, 129(2), 331-344. https://bioone.org/journals/the-wilson-journal-of-ornithology/volume-129/issue-2/16-100.1/Bird-Predation-By-Praying-Mantises-A-Global-Perspective/10.1676/16-100.1.full

- Otte, D., Spearman, L., & Stiewe, M. B. D. (2022). Mantodea Species File. Catalogue of Life Checklist. https://www.catalogueoflife.org/data/taxon/8NKF9

- Pascual, F. (2015). Mantis religiosa, Orden Mantodea. Revista IDE@ – SEA, 47, 1-10. Consultado el 14 de octubre de 2021. http://sea-entomologia.org/IDE@/revista_47.pdf

- Rossoni, S.,& Niven, J. (2020). Prey speed influences the speed and structure of the raptorial strike of a ‘sit-and-wait’ predator. The Royal Society, 16(5). https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0098

- Schwarz, C., Ehrmann, R. (2018). Invasive Mantodea species in Europe. Articulata, 3, 73-90. https://dgfo-articulata.de/downloads/articulata/articulata_33_2018/Articulata_33_Schwarz-Ehrmann.pdf

- Schwarz, C., Mehl, J., & Sommerhalder, J. (2006). Die teufels-blume Idolomantis diabolica (Saussure, 1869)- Teil 1. Terraria, 63-70. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350591722_Die_Teufelsblume_Idolomantis_diabolica_Saussure_1869_-_Teil_1

- The Amateur Entomologist´s Society. (s.f.). Praying Mantids (Order: Mantodea). Consultado el 14 de octubre de 2021. https://www.amentsoc.org/insects/fact-files/orders/mantodea.html

- Zhang, H. L., & Ye, F. (2017). Comparative Mitogenomic Analyses of Praying Mantises (Dictyoptera, Mantodea): Origin and Evolution of Unusual Intergenic Gaps. International journal of biological sciences, 13(3), 367–382. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5370444/

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.