Parasitism: Characteristics, Types and Examples

All living things are meant to relate to each other. However, not all interactions are completely healthy ones. There are some species that are experts in toxic relationships, where only one of the parties gets what they are looking for and their partner (host) is harmed or injured. This relationship is called parasitism.

When talking about parasitism, a past relationship or a person’s name may come to mind, but in the animal kingdom this issue goes far beyond personal misunderstandings and mishaps. If you want to know more about parasitism in nature, keep reading.

Symbiosis and relationships

When we talk about living beings, we have to pay close attention to the relationships that exist between them. In this case, if this relationship is so close that both parties need each other, this is called ‘symbiosis‘. Unfortunately, symbiosis only tells us that two species are very close (not necessarily in a good sense), but it doesn’t tell us anything about their relationship.

Seen in another way, we would call any relationship you have with a specific person symbiosis. In this sense, it wouldn’t matter if they’re your friend, boy or girlfriend, or if you’re enemies: the only thing that counts is that you have some kind of relationship with that person.

Because of this, when talking about symbiosis, we need to be more specific. Since, in relationships, not everything is always fair, a classification is required that reveals who wins or who loses in the interaction. Based on this premise, symbiosis is classified into 4 basic behaviors: commensalism, amensalism, parasitism, and mutualism.

What is parasitism?

Parasitism is the symbiosis that refers to a disproportionate relationship. In this interaction, both the parties don’t benefit, so one wins and the other loses.

This biological mechanism seems similar to what might happen in a dating relationship of “convenience”. While one enjoys travel, money, and expensive gifts, the other wastes money, time, and perhaps even dignity. One party benefits to the detriment of the other.

In nature, we just need to modify this very concept. We simply need to replace ‘money’ with ‘resources’ or, in other words, food. In addition to this, some types of parasitism also fight indirectly for space or reproduction, among other resources available to them in nature.

Thus, in this relationship there are two parties involved: the parasite and the host. The parasite will be in charge of removing the resources or food. Meanwhile, the host is the one that hosts the parasite, in other words, the one that loses.

In this way, the parasite lives at the expense of the host. Furthermore, some parasitic species are so adapted to this form of life that, if the host dies, they die too.

Different parasites

Within parasites there are also classes, or classifications. While these taxa appear behaviorally similar, they aren’t all the same and neither do they act in the same way. Two different classifications are proposed, based on their location in the host and their level of dependence on it.

By its location

If the pathogen is outside the host, it’s called an ectoparasite. If it’s located inside, it’s known as an endoparasite. An endoparasite can either live within cells (intracellular) or in the interstitium (extracellular).

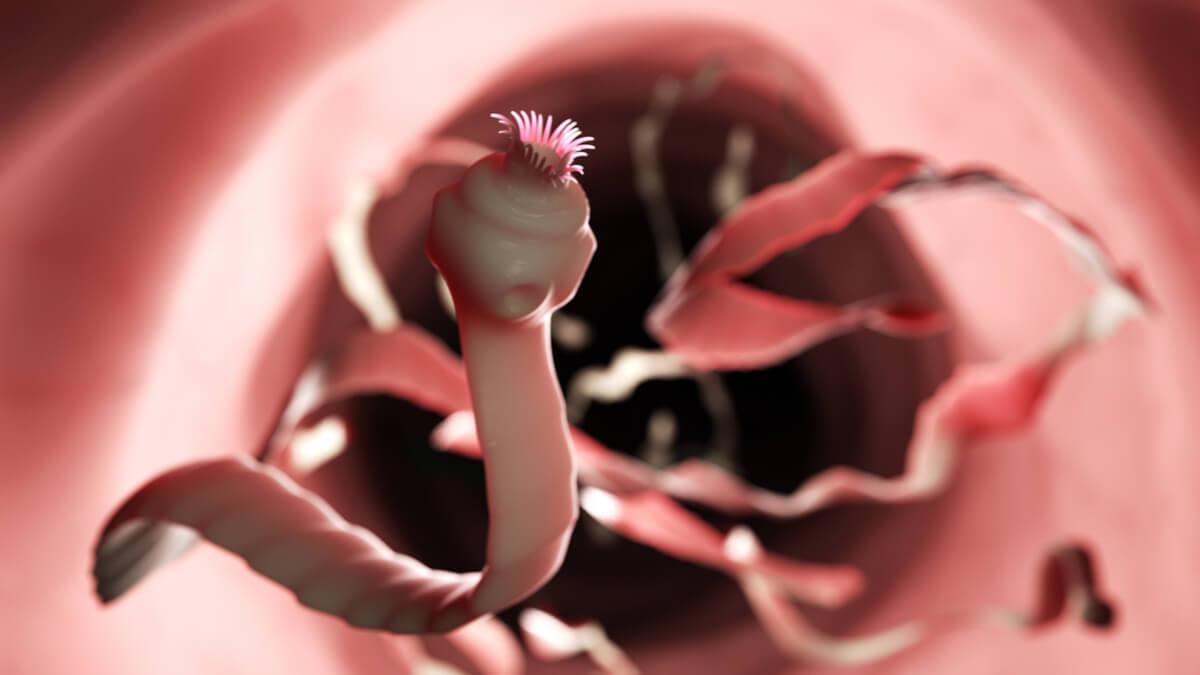

For example, a flea that feeds on the blood of dogs is an ectoparasite, because it’s located outside the host. On the other hand, a tapeworm or Taenia solium is an endoparasite, as it’s found within the body, specifically in the lumen of the intestine.

Because of their level of dependency

When the parasite has the option of feeding on its own apart from feeding on its host, it is classed as facultative. In other words, it’s independent, but, if it needs to, it can get itself a host. However, if it can’t find one, it’s able to survive on its own without any problems.

For example, the nematode Strongyloides stercoralis can live wild on land, yet it’s also capable of infecting humans. It settles in the small intestine of the host and causes a disease called strongyloidiasis.

If, on the other hand, the pathogen can’t live without a host, it’s called obligate. This refers to the fact that the parasite exists, if, and only if, the host is also present. Seen in another way, it isn’t capable of being independent.

This is the case of the protozoan Cryptosporidium hominis, a human intestinal parasite. The infection occurs through infected food, which is full of parasitic cysts waiting to be ingested.

Finally, if, for some reason, the parasite infects a new species that wasn’t its host in the beginning, it’s called accidental. As its name indicates, this interaction occurs by mistake, although it can later be transformed into fixed behavior in that species.

An example of this is the fly Eristalis tenax, which causes myiasis in man, an infection of the skin by fly larvae. This is a type of accidental parasitism because the larvae don’t need the host, but they infect it when, by mistake, they fall into open wounds.

Parasitism and parasitoid

There’s an erroneous belief that parasites can kill their host. However, this doesn’t always happen, at least in cases where the host has a normal immune system. You just have to think about it for a moment: you wouldn’t burn down your own house, right?

Parasitism is successful only if the host survives as well, because otherwise both would be destined to disappear. Because of this, a formal parasite will never kill its host.

The species that kill their host are known as ‘parasitoids’. Since they don’t need their host, they kill it at the first opportunity. Some examples of parasitoids are as follows:

- The Psyllaephagus bliteus insect: This invertebrate injects its eggs into the abdomen of a psyllid, where they grow and develop by eating the organs of their host. Once they have eaten their victim, they leave.

- The Cephalonomia stephanoderis insect: the species injects its eggs into coleopterans, and, in the same way, they eat all the organs and flesh of the host in order to get out.

- Cordyceps fungus: Also known as the parasitic fungus, it affects various insects as it turns them into zombies while consuming them from within.

Parasites can be found almost anywhere, even inside the human body. Maintain your hygiene habits and be careful when eating on the street, unless you want to have a close encounter with them!

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Aristizábal, L. F., Bustillo, A. E., Orozco, J., & Chaves, B. (1998). Efecto del parasitoide Cephalonomia stephanoderis (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae) sobre las poblaciones de Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) durante y después de la cosechaEffect of the parasitoid Cephalonomia stephanoderis (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae) en Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Scolitidae) durante y después de la cosecha. Revista Colombiana de Entomología (Colombia) v. 24 (3-4) p. 149-155.

- Berta, C. D., Virla, E., Colomo, M. V., & Valverde, L. (2000). Efecto en el parasitoide Campoletis grioti de un insecticida usado para el control de Spodoptera frugiperda y aportes a la bionomía del parasitoide. Manejo Integrado de Plagas (CATIE)(no. 57) p. 65-70.

- García, H. H., Gonzalez, A. E., Evans, C. A., Gilman, R. H., & Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. (2003). Taenia solium cysticercosis. The lancet, 362(9383), 547-556.

- Berenguer, J. G. (2007). Manual de Parasitología. Morfología y biología de los parásitos de interés sanitario (Vol. 31). Edicions Universitat Barcelona.

- Ríos-Casanova, L. (2011). ¿QUÉ SON LOS PARASITOIDES?. Revista Ciencia, 62(2), 20-25.

- Zygmunt, D. J., & Stratton, C. W. (1990). Strongyloides stercoralis. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 11(9), 495-497.

- Dávila, P. G., & Fernández, N. R. (2017). El ciclo biológico de los coccidios intestinales y su aplicación clínica. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina UNAM, 60(6), 40-46.

- Herd, R. P. (1990). The changing world of worms: The rise of the cyathostomes and the decline of Strongylus vulgaris. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian, 12(5), 732-736.