Somali Giraffe: Habitat and Characteristics

Written and verified by the biologist Cesar Paul Gonzalez Gonzalez

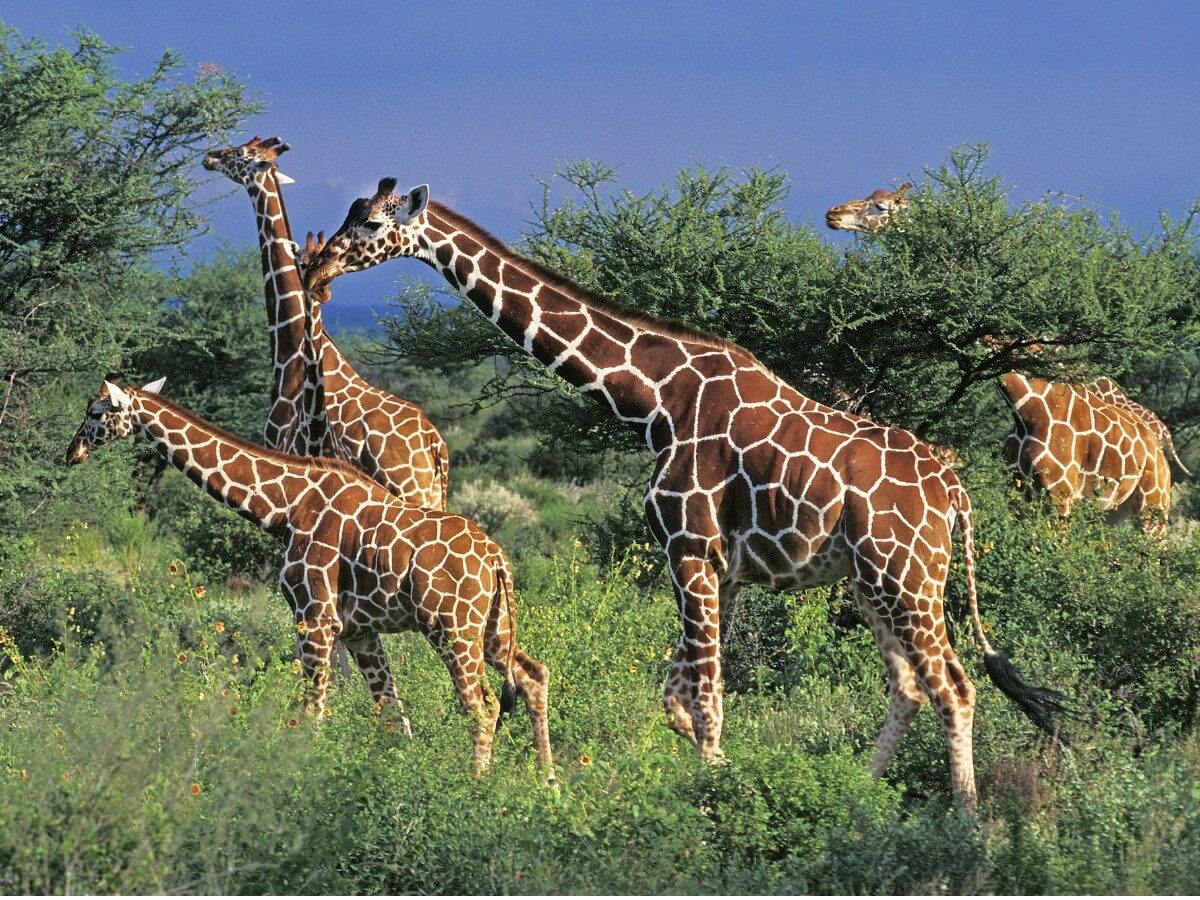

The Somali giraffe is recognized for its long elongated neck, which at some point managed to inspire the most innovative evolutionary theories of its time. Although it’s an endemic species to Africa, you have most likely come across it at a local zoo. Although it may seem like a calm animal, it’s also capable of exhibiting aggressive behavior, which can end in violent fights.

In this article, we’re going to talk about one of the most impressive terrestrial species of all, the Giraffa reticulata, a unique mammal that has a lot to tell. Read on and learn everything about this huge and curious organism.

Habitat and distribution of the Somali giraffe

This mammal can be found in the north and northeast of Kenya, with some small populations in southern Somalia and Ethiopia. In the past, the giraffe was believed to be a single species, distributed throughout Africa, which is far from the truth. In fact, according to an article published in the journal Current Biology, there are four different species of giraffes living in different areas.

The habitats of this vertebrate are wide, desert areas with large amounts of acacia trees. These herds of giraffes coexist with humans, who earn their living by raising livestock and grazing in the same areas.

Characteristics of the Somali giraffe

The giraffe is the tallest land animal in the world, reaching 5.7 meters in height and weighing almost 2 tons. In addition to this, it has a pair of small ossified horns on its head, which are usually surrounded by skin and hair, almost like a pair of “antennae”. In addition, its tail is so thin that it serves as a whip to drive away insects.

Although the sexual dimorphism isn’t very evident, the males are larger than the females, and may even have a second pair of horns. In this regard, an article published in the scientific journal Oecologia mentions that the main difference is how they behave when getting their food. In other words, as the males are more voracious, they’re larger.

These specimens usually have distinctive coloration, consisting of yellow-orange skin, with polygon-shaped spots all over their body. These polygons, in turn, function as a fingerprint, as the same pattern doesn’t repeat itself in other individuals.

Behavior

The species forms herds or groups with 10 or 20 individuals of both sexes. They maintain a social status through hierarchies, as there’s a dominant male who determines his position through fights. During conflicts, males stand side by side, and they begin to beat each other using their necks as whips and their horns as nails.

The results of each battle give them a certain ranking within the herd, so the dominant male is the strongest of all. This is bad news for losers, as they won’t normally be allowed to breed with the females in the group. For this reason, the structure and number of members change constantly, due to the departure and entry of new individuals.

On the other hand, females are more sociable and less aggressive, forming groups without males. However, during each breeding season, they go out in search of a mate, causing the herd to break up.

Somali giraffe feeding

Somali giraffes are herbivorous animals whose main food is the leaves of acacia trees. For this reason, their elongated necks are one of their best tools, as they allow them to reach the highest branches. In addition, they also consume stones sometimes, to supplement the minerals in their diet.

As with other herbivores, this species is ruminant, which means that it spends a lot of time grinding its food, regurgitating it, and regrowing it again. This is necessary, as it’s difficult to obtain the nutrients from the leaves, flowers and pods, so the giraffes try to crush them to make this process more efficient. In fact, it’s for this very reason that they have a 4-chamber stomach.

Reproduction of the Somali giraffe

Giraffes have a curious way of perceiving whether the female is receptive or not, as through the Flehmen response they recognize pheromones that give them away. This happens when they retract their lips and show their gums, exposing their vomeronasal organ, which is in charge of detecting odors. In other words, males do urine tests that let them know if the potential partner is fertile.

When the male detects that the female is ready, he begins to court her in order to mate. It does this by grabbing its tail, as if asking for permission. The counterpart can either ignore or accept it and also hold the prospect’s tail. In this way, the couple forms for at least one mating season.

The smell of this animal plays a very important role in reproduction. This is because, through this sense, individuals can recognize if a female is more fertile than others, allowing them to select the fittest. Choosing the best suitor is essential for this mammal, as it can only mate every 20 to 30 months, thus ensuring the success of its litter.

Caring for the couple

The specimens of this species are considered polygamous, because they don’t maintain a single partner for life. In fact, it’s for this reason that males will prevent any other suitor from approaching the female at all costs until her calf has been born.

Gestation and birth

The gestation will last around 450 days and the birth will take place between the months of May and August. The mother can give birth while walking, and so her calf will fall to the ground from a height of 2 meters. They don’t suffer any serious injury. In fact, right after falling, they get up on their own and begin to breastfeed.

Breeding care and independence

During the first weeks, the little ones are cared for by their mothers incessantly. However, from the month of life, the females of the group divide the work by forming nurseries, in which they concentrate the newborns. Thanks to this, they can look for water and food without leaving their young alone.

For their part, the young will become independent when they reach 4 or 5 years of age. In fact, because they’re animals that follow a hierarchy, the males leave in search of a group where they can be the dominant ones. This induces them to separate and be lonely for a time, at least until they find a herd or form their own.

Conservation status

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, this mammal is listed as a threatened species. This is due to its small and fragmented population, which restricts it to specific areas in Africa. What’s more, their habitat has been invaded and destroyed, due to the increase in livestock activities in the area, as a result of the number of local inhabitants.

In addition, due to its enormous size, this giraffe is hunted for its meat. In fact, at least 30% of the communities close to their natural environment have consumed giraffe meat. At the same time, the villagers hunt this species as part of their customs, which gives them a better social status within their community.

Despite the friendly appearance of giraffes, all of them are classified in some category of risk. It’s for this reason that zoos function as a type of “Noah’s Ark”, giving them an extra chance to evade extinction. Unfortunately, today some species are more endangered in their natural habitat than in captivity.

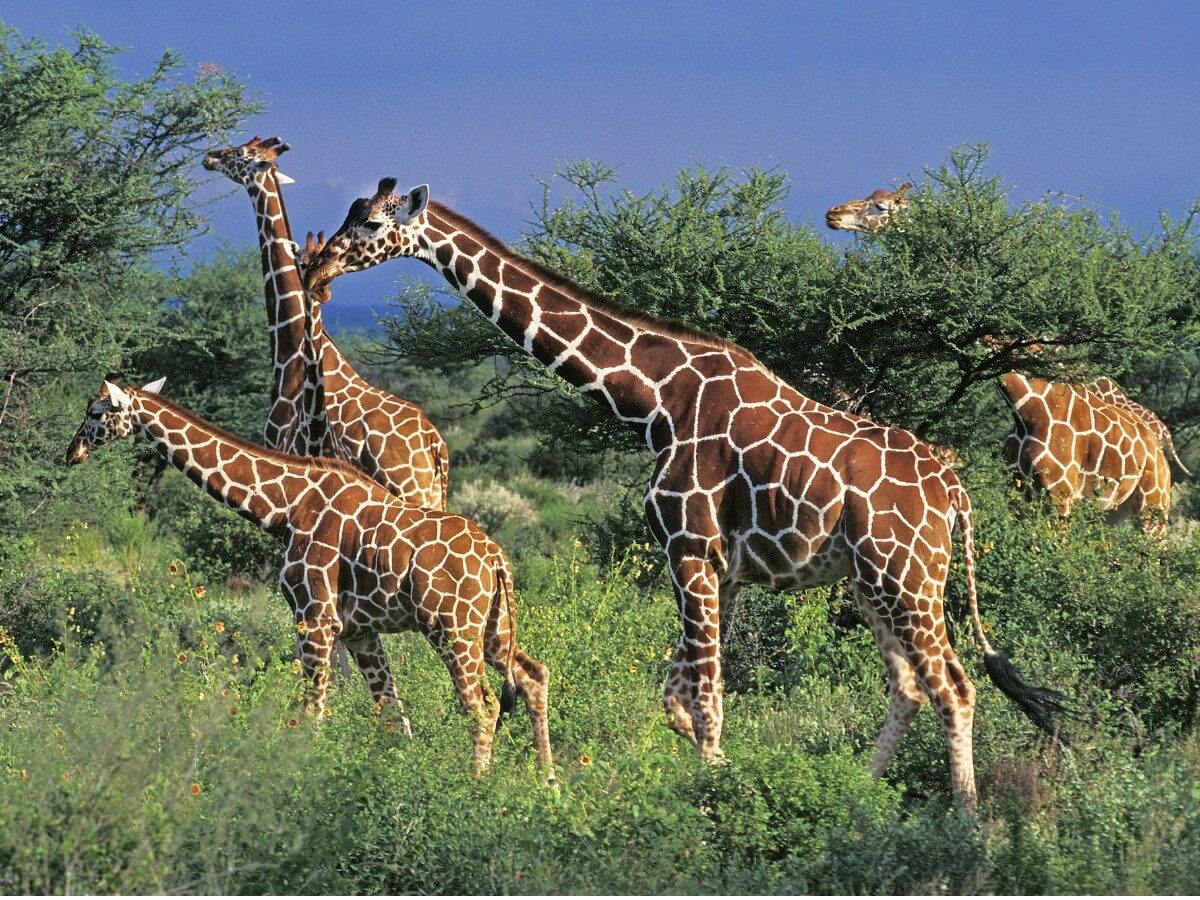

The Somali giraffe is recognized for its long elongated neck, which at some point managed to inspire the most innovative evolutionary theories of its time. Although it’s an endemic species to Africa, you have most likely come across it at a local zoo. Although it may seem like a calm animal, it’s also capable of exhibiting aggressive behavior, which can end in violent fights.

In this article, we’re going to talk about one of the most impressive terrestrial species of all, the Giraffa reticulata, a unique mammal that has a lot to tell. Read on and learn everything about this huge and curious organism.

Habitat and distribution of the Somali giraffe

This mammal can be found in the north and northeast of Kenya, with some small populations in southern Somalia and Ethiopia. In the past, the giraffe was believed to be a single species, distributed throughout Africa, which is far from the truth. In fact, according to an article published in the journal Current Biology, there are four different species of giraffes living in different areas.

The habitats of this vertebrate are wide, desert areas with large amounts of acacia trees. These herds of giraffes coexist with humans, who earn their living by raising livestock and grazing in the same areas.

Characteristics of the Somali giraffe

The giraffe is the tallest land animal in the world, reaching 5.7 meters in height and weighing almost 2 tons. In addition to this, it has a pair of small ossified horns on its head, which are usually surrounded by skin and hair, almost like a pair of “antennae”. In addition, its tail is so thin that it serves as a whip to drive away insects.

Although the sexual dimorphism isn’t very evident, the males are larger than the females, and may even have a second pair of horns. In this regard, an article published in the scientific journal Oecologia mentions that the main difference is how they behave when getting their food. In other words, as the males are more voracious, they’re larger.

These specimens usually have distinctive coloration, consisting of yellow-orange skin, with polygon-shaped spots all over their body. These polygons, in turn, function as a fingerprint, as the same pattern doesn’t repeat itself in other individuals.

Behavior

The species forms herds or groups with 10 or 20 individuals of both sexes. They maintain a social status through hierarchies, as there’s a dominant male who determines his position through fights. During conflicts, males stand side by side, and they begin to beat each other using their necks as whips and their horns as nails.

The results of each battle give them a certain ranking within the herd, so the dominant male is the strongest of all. This is bad news for losers, as they won’t normally be allowed to breed with the females in the group. For this reason, the structure and number of members change constantly, due to the departure and entry of new individuals.

On the other hand, females are more sociable and less aggressive, forming groups without males. However, during each breeding season, they go out in search of a mate, causing the herd to break up.

Somali giraffe feeding

Somali giraffes are herbivorous animals whose main food is the leaves of acacia trees. For this reason, their elongated necks are one of their best tools, as they allow them to reach the highest branches. In addition, they also consume stones sometimes, to supplement the minerals in their diet.

As with other herbivores, this species is ruminant, which means that it spends a lot of time grinding its food, regurgitating it, and regrowing it again. This is necessary, as it’s difficult to obtain the nutrients from the leaves, flowers and pods, so the giraffes try to crush them to make this process more efficient. In fact, it’s for this very reason that they have a 4-chamber stomach.

Reproduction of the Somali giraffe

Giraffes have a curious way of perceiving whether the female is receptive or not, as through the Flehmen response they recognize pheromones that give them away. This happens when they retract their lips and show their gums, exposing their vomeronasal organ, which is in charge of detecting odors. In other words, males do urine tests that let them know if the potential partner is fertile.

When the male detects that the female is ready, he begins to court her in order to mate. It does this by grabbing its tail, as if asking for permission. The counterpart can either ignore or accept it and also hold the prospect’s tail. In this way, the couple forms for at least one mating season.

The smell of this animal plays a very important role in reproduction. This is because, through this sense, individuals can recognize if a female is more fertile than others, allowing them to select the fittest. Choosing the best suitor is essential for this mammal, as it can only mate every 20 to 30 months, thus ensuring the success of its litter.

Caring for the couple

The specimens of this species are considered polygamous, because they don’t maintain a single partner for life. In fact, it’s for this reason that males will prevent any other suitor from approaching the female at all costs until her calf has been born.

Gestation and birth

The gestation will last around 450 days and the birth will take place between the months of May and August. The mother can give birth while walking, and so her calf will fall to the ground from a height of 2 meters. They don’t suffer any serious injury. In fact, right after falling, they get up on their own and begin to breastfeed.

Breeding care and independence

During the first weeks, the little ones are cared for by their mothers incessantly. However, from the month of life, the females of the group divide the work by forming nurseries, in which they concentrate the newborns. Thanks to this, they can look for water and food without leaving their young alone.

For their part, the young will become independent when they reach 4 or 5 years of age. In fact, because they’re animals that follow a hierarchy, the males leave in search of a group where they can be the dominant ones. This induces them to separate and be lonely for a time, at least until they find a herd or form their own.

Conservation status

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, this mammal is listed as a threatened species. This is due to its small and fragmented population, which restricts it to specific areas in Africa. What’s more, their habitat has been invaded and destroyed, due to the increase in livestock activities in the area, as a result of the number of local inhabitants.

In addition, due to its enormous size, this giraffe is hunted for its meat. In fact, at least 30% of the communities close to their natural environment have consumed giraffe meat. At the same time, the villagers hunt this species as part of their customs, which gives them a better social status within their community.

Despite the friendly appearance of giraffes, all of them are classified in some category of risk. It’s for this reason that zoos function as a type of “Noah’s Ark”, giving them an extra chance to evade extinction. Unfortunately, today some species are more endangered in their natural habitat than in captivity.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Horová, E., Brandlová, K., & Gloneková, M. (2015). The first description of dominance hierarchy in captive giraffe: not loose and egalitarian, but clear and linear. PloS one, 10(5), e0124570.

- Takagi, N., Saito, M., Ito, H., Tanaka, M., & Yamanashi, Y. (2019). Sleep‐related behaviors in zoo‐housed giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata): Basic characteristics and effects of season and parturition. Zoo biology, 38(6), 490-497.

- Muneza, A., Doherty, J. B., Hussein, A. A., Fennessy, J., Marais, A., O’Connor, D., & Wube, T. (2018). Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. reticulata. The IUCN Red List of Threatend Species.

- Seeber, P. A., Ciofolo, I., & Ganswindt, A. (2012). Behavioural inventory of the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). BMC research notes, 5(1), 1-9.

- Ginnett, T. F., & Demment, M. W. (1997). Sex differences in giraffe foraging behavior at two spatial scales. Oecologia, 110(2), 291-300.

- Shorrocks, B. (2016). The giraffe: biology, ecology, evolution and behaviour. John Wiley & Sons.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.